Minneapolis Modernism: the story of the Walker Art Center

Walker Art Center. Photo Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society.

Name of Building/Site:

Walker Art Center

Building/Site Address:

1710 Lyndale Avenue South (1927-1971)

725 Vineland Place (1971-Present)

Minneapolis, MN 55403

Designation:

None apply

Summary:

The Walker Art Center is a destination for culture and art in the Twin Cities. Known for multifaceted public programming and ambitious exhibitions, the Walker is also responsible for introducing Modernism to Minneapolis. Through key individuals, architectural evolutions, and the city’s support, the Walker—a contemporary icon—occupies a central position in the architectural canon of Midwest Modernism.

Author:

Mary Dahlman Begley is an architectural designer, researcher, and writer living in Minneapolis. December, 2020.

WC: 2359

Construction Dates:

1966-1971

Architectural and Other Designer(s):

Edward Larrabee Barnes (architect), Mildred Friedman (interior design)

WALKER ART GALLERY

In 1879, thirteen years after the incorporation of Minneapolis as a city, lumber baron Thomas Barlow Walker opened a gallery in his house on Hennepin Avenue. (See figure 1) With this gesture, T.B. Walker created the first art gallery west of the Mississippi and the first physical location of what would become the Walker Art Center. Walker’s taste skewed Romantic, with lush materials and intricate details in the architecture and interiors of the Walker Art Gallery. As Walker’s fortune continued to grow, he expanded his collection as well as the space; by 1915 the home gallery included 15 rooms.

In 1927 the first purpose-built building of the Walker Art Gallery opened. (Figure 2) This Moorish-style building, designed by long-standing local firm Long and Thorshov, stood on the current site of the Walker Art Center, adjacent to two of Minneapolis’ main thoroughfares: Hennepin and Lyndale Avenues. (Figure 3) The site’s marshy terrain was built up with soil removed for the road construction. The symmetrical plan was simple, the ornamentation elaborate, and the style a marker of Walker’s status as a baron of the Romantic period. Revivalist Architecture was popular throughout the 18th and 19th centuries in the United States, as the young, rapidly modernizing nation looked to the past great empires for inspiration. Walker was a cosmopolitan connoisseur and the design of the building drew from a range of stylistic references: Arabesque motifs in the terracotta facade add texture and recall the western Islamic world, the dramatic pediment at entry and flourishing double stair in the interior signal a Baroque sensibility, yet the symmetry and relatively unembellished interiors speak to proto-modern design and the building’s utility as an art gallery. Walker Art Gallery operated as such until 1939, when a federal program prompted a shift in the institution’s trajectory.

Walker Art Center

Building/Site Address:

1710 Lyndale Avenue South (1927-1971)

725 Vineland Place (1971-Present)

Minneapolis, MN 55403

Designation:

None apply

Summary:

The Walker Art Center is a destination for culture and art in the Twin Cities. Known for multifaceted public programming and ambitious exhibitions, the Walker is also responsible for introducing Modernism to Minneapolis. Through key individuals, architectural evolutions, and the city’s support, the Walker—a contemporary icon—occupies a central position in the architectural canon of Midwest Modernism.

Author:

Mary Dahlman Begley is an architectural designer, researcher, and writer living in Minneapolis. December, 2020.

WC: 2359

Construction Dates:

1966-1971

Architectural and Other Designer(s):

Edward Larrabee Barnes (architect), Mildred Friedman (interior design)

WALKER ART GALLERY

In 1879, thirteen years after the incorporation of Minneapolis as a city, lumber baron Thomas Barlow Walker opened a gallery in his house on Hennepin Avenue. (See figure 1) With this gesture, T.B. Walker created the first art gallery west of the Mississippi and the first physical location of what would become the Walker Art Center. Walker’s taste skewed Romantic, with lush materials and intricate details in the architecture and interiors of the Walker Art Gallery. As Walker’s fortune continued to grow, he expanded his collection as well as the space; by 1915 the home gallery included 15 rooms.

In 1927 the first purpose-built building of the Walker Art Gallery opened. (Figure 2) This Moorish-style building, designed by long-standing local firm Long and Thorshov, stood on the current site of the Walker Art Center, adjacent to two of Minneapolis’ main thoroughfares: Hennepin and Lyndale Avenues. (Figure 3) The site’s marshy terrain was built up with soil removed for the road construction. The symmetrical plan was simple, the ornamentation elaborate, and the style a marker of Walker’s status as a baron of the Romantic period. Revivalist Architecture was popular throughout the 18th and 19th centuries in the United States, as the young, rapidly modernizing nation looked to the past great empires for inspiration. Walker was a cosmopolitan connoisseur and the design of the building drew from a range of stylistic references: Arabesque motifs in the terracotta facade add texture and recall the western Islamic world, the dramatic pediment at entry and flourishing double stair in the interior signal a Baroque sensibility, yet the symmetry and relatively unembellished interiors speak to proto-modern design and the building’s utility as an art gallery. Walker Art Gallery operated as such until 1939, when a federal program prompted a shift in the institution’s trajectory.

|

Figure 1.

In 1879, art collector and lumber baron Thomas Barlow Walker opened a public gallery in his house at 802 Hennepin Ave. This collection and location, the Walker Art Gallery, is the progenitor of the Walker Art Center. Interior, Walker Art Gallery, Minneapolis [photoprint]. (c. 1918). Minnesota Historical Society. http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10753847 |

Figure 2.

The first purpose-built building of the Walker Art Gallery opened in 1927. The Revivalist, Moorish style building was designed by Long and Thorshov. Walker Art Center, Lyndale at Hennepin, Minneapolis [photonegative]. (1926). Minnesota Historical Society. http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10865654 |

WALKER ART CENTER

The Walker Art Gallery became the Walker Art Center through city strategic goals, public funds, the support of the Walker family, and the vision of Daniel S. Defenbacher. Defenbacher worked for the Federal Art Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) establishing art centers across the country. In 1938 Minnesota Art Council (MAC) contacted Defenbacher to assist with their initiative. Archie Walker, T.B.’s son and then president of the Walker Art Gallery, supported MAC’s initiative. Defenbacher was interested; MAC raised the initial $5,000 required to leverage $35,000 of WPA salaries and support, and the Walker Art Gallery offered up their large facility and collection for the establishment of the center. Walker Art Center opened on January 4, 1940, with Defenbacher as its first Director.

Defenbacher articulated a vision for the Walker Art Center (WAC) that would bring art and people together. WAC’s educational focus was supported by the WPA, and in the early years an art school operated in the building. WPA funding proved unreliable, and as WWII dragged on the institution suffered from losing personnel to the War effort. WPA support of the Center was terminated in 1943 and the Walker Foundation assumed financial responsibility of WAC. This led to the purchase of the museum’s first piece of modern art in 1942: Franz Marc’s Die grossen blauen Pferde (The Large Blue Horses) (1911). These early years set the tone for WAC as an institution dedicated to the cutting edge of art, design, and public-private partnerships.

EVERYDAY ART

In the 1940s, the Walker introduced ideas of Modernist design to Minneapolis through a new gallery, the Everyday Art Gallery. The Everyday Art Gallery drew inspiration from early Modernist thinkers, such as the Werkbund, formed in 1909 Germany to promote good design. This association of artists, architects, and designers contributed to material and design exploration that created an aesthetic language for Modernist design. Gropius, Le Corbusier, and Mies van der Rohe furthered this aesthetic language, and through their influence Philip Johnson in the 1930s curated a program at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) that symbolically welcomed Modernism to the US. In 1940, Eliot Noyes of MoMA held the first of many open competitions to stimulate new ideas in furniture, fabric, and lamps. The momentum of this movement of Modernist design at the scale of the home inspired Defenbacher to formulate a proposal in 1940 for a “consumer’s art gallery.”

In 1944, Defenbacher appointed Hilde Reiss as the curator of the new Everyday Art Gallery. Reiss and Defenbacher shared a commitment to “useful art” - a principle of industrial design in the Modern era that posits design as the way an object is elevated from a product to an art form. Reiss was introduced to Modern design when she studied architecture under Walter Gropius at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany from 1930 to 1932. Reiss moved to New York and taught at the Design Laboratory, a project of the WPA, where she met William Friedman, who would become her husband and colleague at the Walker Art Center. The couple were both hired by Defenbacher in 1944 (Friedman as Assistant Director in charge of Exhibitions). Reiss’ training at the Bauhaus and work experience in both public and private sectors informed her design ethic, which she described as “straightforward and practical.” This sensibility translated well to Minneapolis, where the Everyday Art Gallery - through the display of consumer products - brought High Modernism to the level of the everyday.

In the 1940s, the Walker introduced ideas of Modernist design to Minneapolis through a new gallery, the Everyday Art Gallery. The Everyday Art Gallery drew inspiration from early Modernist thinkers, such as the Werkbund, formed in 1909 Germany to promote good design. This association of artists, architects, and designers contributed to material and design exploration that created an aesthetic language for Modernist design. Gropius, Le Corbusier, and Mies van der Rohe furthered this aesthetic language, and through their influence Philip Johnson in the 1930s curated a program at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) that symbolically welcomed Modernism to the US. In 1940, Eliot Noyes of MoMA held the first of many open competitions to stimulate new ideas in furniture, fabric, and lamps. The momentum of this movement of Modernist design at the scale of the home inspired Defenbacher to formulate a proposal in 1940 for a “consumer’s art gallery.”

In 1944, Defenbacher appointed Hilde Reiss as the curator of the new Everyday Art Gallery. Reiss and Defenbacher shared a commitment to “useful art” - a principle of industrial design in the Modern era that posits design as the way an object is elevated from a product to an art form. Reiss was introduced to Modern design when she studied architecture under Walter Gropius at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany from 1930 to 1932. Reiss moved to New York and taught at the Design Laboratory, a project of the WPA, where she met William Friedman, who would become her husband and colleague at the Walker Art Center. The couple were both hired by Defenbacher in 1944 (Friedman as Assistant Director in charge of Exhibitions). Reiss’ training at the Bauhaus and work experience in both public and private sectors informed her design ethic, which she described as “straightforward and practical.” This sensibility translated well to Minneapolis, where the Everyday Art Gallery - through the display of consumer products - brought High Modernism to the level of the everyday.

|

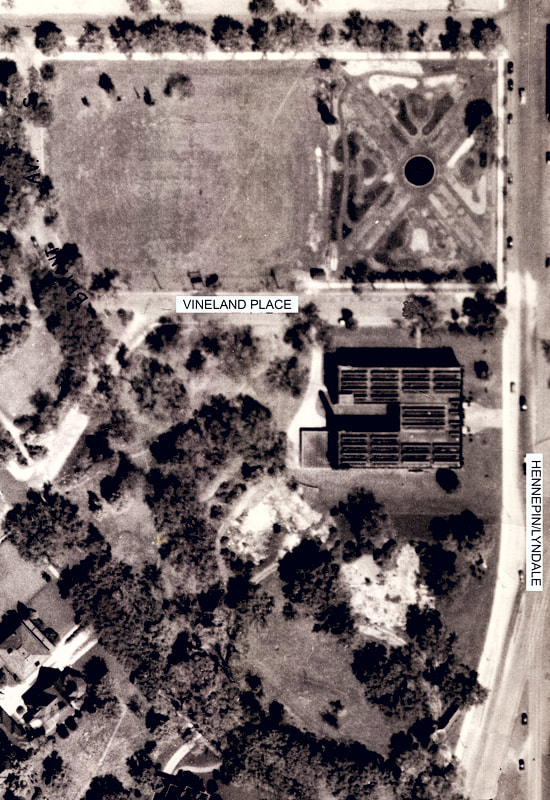

Figure 3.

This aerial photo from 1938 shows the 1927 building of the Walker Art Center and, to the north, the park board maintained Kenwood Gardens. [Aerial photograph] [cropped] (1938). Minnesota Historical Aerial Photographs Online. http://geo.lib.umn.edu/minneapolis/1938/07-B-N.jpg |

Figure 4.

The 1944 facade update was designed by Magney, Tusslar, and Setter. The broad, planar facade opened to the largely unrenovated interior for a Moderne style that served the Walker Art Center until the late 1960s. Jacobson, R. (1963). Institute, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis [photoprint]. Minnesota Historical Society. http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=11362637 |

MODERN MAKEOVER

As the Walker Art Center’s agenda for art and design grew into the Modern period, it followed that the architecture required similar updating. In 1944 - the same year that WAC displayed an exhibition about Le Corbusier - the original, 1927 facade was replaced. (Figure 4) The ornamental features of the Long & Thorshov facade were cracked and faded. Local firm Magney, Tussllar, and Setter were hired for a “face-lifting operation” - the traditional French windows from the 1927 design remained, as the terracotta facade was removed and replaced with understated Mankato stone and Coldspring granite. The new look was streamlined, planar, and designed in the Moderne style. Moderne, an early iteration of Modernism, is typically indicated by eclectic coexistence of traditional and Modern architectural styles. WAC’s traditional interior was left largely untouched, save for new design features in the Everyday Art Gallery. The billboard front of the new building faced busy Hennepin Avenue and signalled the Center’s projection of Modern style into Minneapolis.

Defenbacher and his successor as director, H. Harvard Arnason (1951-1961) continued WAC’s transition into the Modern. Defenbacher commissioned a series of case study houses, built full scale on the Walker grounds to display Modern design concepts. Arnason lived in Idea House II (opened 1947), designed by Hilde Reiss, as he expanded WAC’s collection of Modern and contemporary art. In the 1950s, as the post-War consumer era began, Modern design spread across the country. Martin and Mildred “Mickey” Friedman were steeped in the design tradition of mid-century California, where the Eames led the charge of tying together art, design, and commercial objects in a visual style that would prove enduringly influential. This strain of the Modernist movement - design that is accessible and useful - can be linked to the Everyday Art Gallery. As such, the Friedmans were a natural fit for the Walker when Martin became director in 1961.

By the 1960s, WAC’s northwest corner had sunk nearly 13” into the marshy ground of Lowry Hill. The board of directors hired Edward Larrabee Barnes for a remodel in 1966. Upon inspection of the sinking foundation, Barnes and the board determined that a new building was in order. This building, designed by Barnes and opened in 1971, is a marvel of Late Modernism and the backdrop to the Walker’s successful transition to its contemporary success.

|

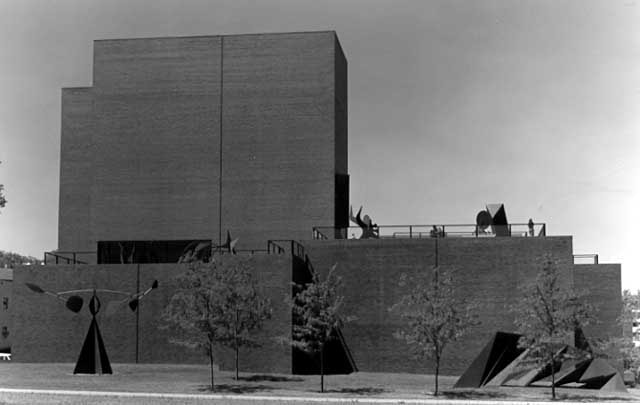

Figure 5. The Edward Larrabee Barnes designed building for the Walker Art Center opened in 1971. An excellent example of Late Modernism, the building’s plum-colored brick exterior encloses a helical plan of loftlike galleries in the central tower. Walker Art Center, 1710 Lyndale Avenue South, Minneapolis [photoprint]. (1982). Minnesota Historical Society. http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10725445 |

LATE MODERNISM

Edward Larrabee Barnes studied architecture under Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, alongside noted architect I.M. Pei. In 1966, when Barnes received the commission for his first museum design, Modernism was in its Late period. Late Modern style is characterized by exaggerated structure, repetition of forms, and rhetorical concepts that play with paradox and experience. Pei’s Everson Museum of Art at Syracuse (opened 1968) and Barnes’ design for the Walker Art Center, demonstrate these ideas well. Volumetric and boxy, these buildings had few windows and subdued material palettes. In this sense, the architecture of the 1971 WAC building emulates the minimalist objects acquired by the Walker in this period, by the likes of Donald Judd and Dan Flavin. This style favors dimensional experience - the composition of objects changes as you walk around and observe shifting spatial relationships.

The new building opened on May 15, 1971. (Figure 5) In Design Quarterly Barnes and Mildred Friedman (interior design of the building) described the design intent: “We are trying to create architecture that does not compete with art- to put the priorities in the right order.” Barnes designed with care for the flow of the building. The resulting building, six stories above ground, wraps loftlike, stepped galleries around a central core. This circulation scheme, typified by the Guggenheim Museum, allows visitors to bypass galleries in a helical plan. The office and service spaces are separate from the central circulation, privileging the visitor flow. As the visitor moves up the spaces, scale changes of the gallery volumes are made perceptible by subtle formal moves: a skylight, a small stair, and increasing height from ten feet in Gallery 1 up to 18 feet in Gallery 6. Gallery 6 contains a glass wall, showing off three terraces which culminate the sequence of expansion by blowing the roof off, using the city and sky as backdrop for the art displayed outside.

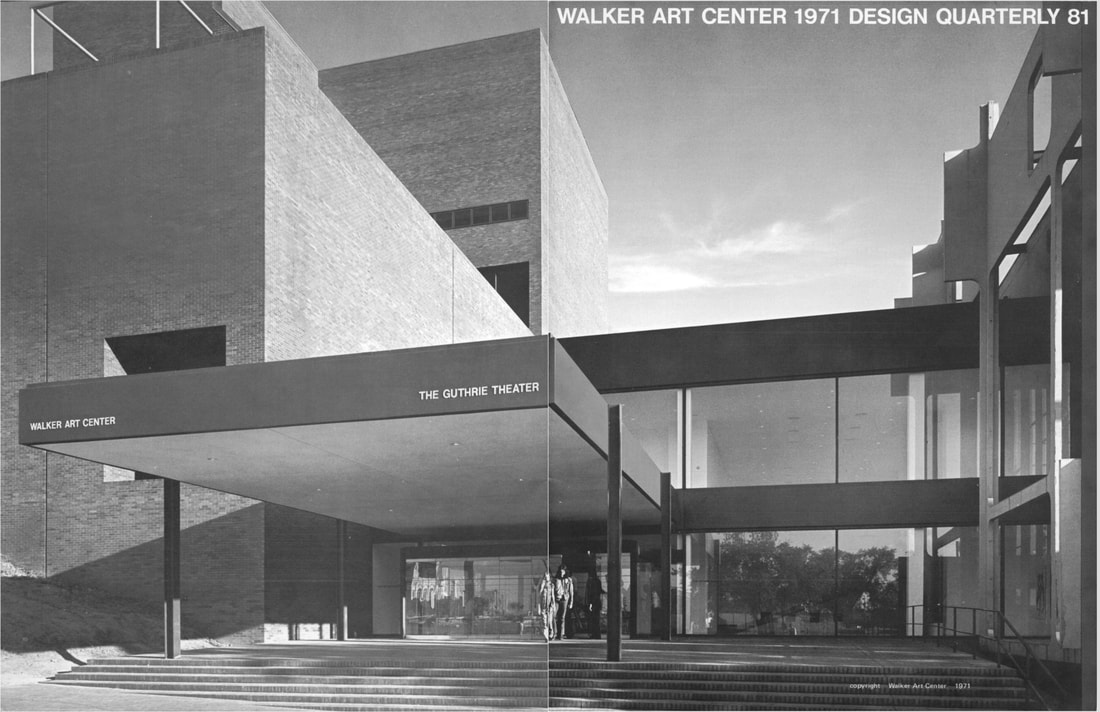

A new entrance for the Walker, on the north side, rerouted the visitors off busy Hennepin and Lyndale - now a freeway entry - to the quieter Vineland Place. This new entrance was shared between the Walker and Tyrone Guthrie Theater, designed by Ralph Rapson. (Figure 6) The Guthrie’s perforated facade is a playful counterpoint to the Walker’s plum-brick exterior. The monotone facade material wraps the Walker within itself, creating a continuous envelope. This delicate balancing act was more than just aesthetic, as the Guthrie Main Lobby and Box Office and upper level Balcony and Lobby bled into the plan of the Walker, sharing space, audience, and establishing a cultural center for the city.

Peter Blake, a prominent architectural critic, wrote in 1974 that the Walker is “quite possibly, the finest American museum for modern art in operation today.” Blake’s review of the building’s “virtuosic” architectural design highlights the building’s ability to highlight artwork displayed within. This is a true strength of Barnes’ design, and the new building gave the Walker Art Center the room it needed to grow. According to Blake, the Walker’s 1971 building contributed to “shift[ing] the center of gravity of the American art world from New York to this rather intriguing little Midwestern city.”

Figure 6.

The cover of Design Quarterly magazine depicts the shared entrance to the 1971 Walker Art Center building, designed by Edward Larrabee Barnes and the 1969 Guthrie Theater building, designed by Ralph Rapson. Design Quarterly was originally titled Everyday Art Quarterly, and was published by the Walker Art Center until 1996.

Barnes, E.L. & Friedman, M.S. [cover image] (1971). Walker Art Center. Design Quarterly, (no 81), pp.1-22. http://www.jstor.com/stable/4047412

The cover of Design Quarterly magazine depicts the shared entrance to the 1971 Walker Art Center building, designed by Edward Larrabee Barnes and the 1969 Guthrie Theater building, designed by Ralph Rapson. Design Quarterly was originally titled Everyday Art Quarterly, and was published by the Walker Art Center until 1996.

Barnes, E.L. & Friedman, M.S. [cover image] (1971). Walker Art Center. Design Quarterly, (no 81), pp.1-22. http://www.jstor.com/stable/4047412

INTO THE POSTMODERN PERIOD

Barnes worked with the Walker twice more in the 1980s. In 1984, an addition to the building including a new gallery below ground level on the east side, a 70-seat lecture room, new print study room, extended book shop, and youth education facilities opened. An addition to the south provided more office, shop, and storage space. The addition of these programs recommitted the Walker Art Center to their mission, as articulated in 1976 when WAC became a public institution, to “champion the production of new art and preserve historically important cultural artifacts.” The new programs added in the 1984 addition allowed the architecture to more closely reflect the Walker’s mission.

Barnes and the Friedmans had long had their eyes on the land across Vineland Place, to the North of the Walker. In the early 20th century, this land was Armory Gardens, maintained by the Minnesota National Guard. From 1934 to the 1960s, the Minneapolis Park Board maintained the formally designed space, then known as Kenwood Gardens. During the construction of Interstate 94 over Hennepin and Lyndale, the gardens were used for equipment storage. Since the completion of construction in the 1970s, the land sat empty. In 1981 David Fischer became superintendent of Minneapolis Park Board. He too had his eyes on the former Kenwood Gardens land. Martin Friedman and David Fischer brought about the collaboration of an institution and a public agency - another public-private partnership that shaped the Walker’s history- to create a novel, adventurous, and ultimately cherished park space.

The Minneapolis Sculpture Garden was designed by Barnes, who by then was in what architectural critic and professor emeritus at University of Minnesota Tom Fisher described as his Postmodern phase. The symmetrical garden contains four rooms, defined by plants and a cross axis. (Figure 7) This design references Italian gardens and Renaissance gardens, in stark contrast to the abstract Late Modernist building. The Garden terminated in the north with a lake surrounding Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s Postmodern Pop art sculpture “Spoonbridge and Cherry,” commissioned for the Garden. This art piece has become an icon for the city of Minneapolis, neatly symbolising the collaboration between an art museum and the City of Minneapolis that created the Garden.

By the 2000s, the Walker had grown beyond its Modern era footprint. The Guthrie Theater had plans to be demolished, and the North American Life and Casualty Building site to the south was purchased by the Walker. Kathy Halbreich, then director of the Walker, oversaw the selection process for a new addition. Herzog and de Meuron, a contemporary architecture firm from Basel, were selected. In 2005 the new addition opened, a crinkly, shadowless envelope wraps an irregular volume. The pristine skin of this new addition meets the 1971 building through a glass link running parallel to Hennepin/Lyndale.

The Herzog and de Meuron addition complicates the neatness of Barne’s Late Modernist design, yet demonstrates the Walker’s commitment to continual adaptation to contemporary times, retaining its position as a cultural center in Minneapolis. It is through this adaptation that the Walker was able to relate to the Modernist movement in architecture throughout its evolution: from Moderne, to Late Modern, and out the door to a Postmodern Garden. With influences from Germany to California, strategic partnerships with public entities, and the thoughtfulness of numerous designers and curators, the Walker introduced Modernism to Minneapolis.

|

Figure 7. This aerial photo from 1993 shows the 1988 Minneapolis Sculpture Garden, built to the north of the Walker Art Center and designed by Edward Larrabee Barnes. The Tyrone Guthrie Theater, designed by Ralph Rapson, sits directly to the west of the Walker Art Center’s position on the corner of Vineland Place and Hennepin/Lyndale. [Aerial photograph] [cropped] (1993). Minnesota Historical Aerial Photographs Online. http://geo.lib.umn.edu/minneapolis/1903/07-B-N.jpg |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(1948). Museum Facade, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Progressive Architecture, February 1948. Pp 48-49. https://usmodernist.org/index-pa.htm

(1949). Where to See Everyday Art. Everyday Art Quarterly, Winter 1949-1950 (No. 13), pp. 1-11. http://www.jstor.com/stable/4047161

About: Mission & History. Walker Art. https://walkerart.org/about/mission-history

Barnes, Edward Larrabee and Mildred S. Friedman. (1971). Walker Art Center 1971. Design Quarterly, (No. 9), pp. 1-22. http://www.jstor.com/stable/4047412

Blake, Peter. (1974). Brick-on-brick and white-on-white: the Walker Art Center may be the best modern museum in the U.S. Architecture plus volume 2 (Issue 4).

Bergdoll, Barry. (2009). I.M. Pei, Marcel Breuer, Edward Larrabee Barnes, and the New American Museum Design of the 1960s. Studies in the History of Art (Vol 73, Symposium Papers L: A Modernist Museum in Perspective: The East Building, National Gallery of Art), pp. 106-123. http://www.jstor.com/stable/42622475

Comazzi, John and Margaret Werry. (2008) The Walker Art Center + The Tyrone Guthrie Theater, Minneapolis: Two Views. Journal of Architectural Education (Vol. 61, No. 4, Performance/Architecture), pp. 131-135. http://www.jstor.com/stable/40480873

Dill, Emma. (2018, April 30). Walker Art Center. MNopedia. https://www.mnopedia.org/place/walker-art-center

Fischer, Mark (producer). (2013, May 26). Minneapolis Sculpture Garden [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.mnvideovault.org/index.php?id=24340&select_index=0&popup=yes#0.

Fox, Margalit. (2016, May 13). Martin Friedman, Whose Vision Shaped Walker Art Center, Dies at 90. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/14/arts/design/martin-friedman-whose-vision-shaped-walker-art-center-dies-at-90.html

Madison, Cathy. (2005). Walker Art Center: Art spaces. Scala Publishers Limited.

Ruddy, Martha. (1998, November). Daniel S. Defenbacher Papers, 1939-1951. [Biography, description]. WAC RG1 S1 (94.09.DO). https://s3.amazonaws.com/wac-imgix/cms/DSD_FA.pdf

Smith, David C. (2013, May 30). Minneapolis Sculpture Garden is 25. Retrieved from https://minneapolisparkhistory.com/2013/05/30/minneapolis-sculpture-garden-is-25/

Vuchetich, Jill. (2014, October 28). Ghost Building: Walker Galleries 1927. Walker Reader. https://walkerart.org/magazine/ghost-building-walker-galleries-1927

Vuchetich, Jill. (2014, October 8). Walker History: Shall We Take It? The Walker’s Founding Question. Walker Reader. https://walkerart.org/magazine/public-art-center-defenbacher

Yardley, Willian. (2014, September 9). Mildred Friedman, 85, Dies; Curator Elevated Design and Architecture. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/10/arts/design/mildred-friedman-design-curator-dies-at-85.html

(1948). Museum Facade, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Progressive Architecture, February 1948. Pp 48-49. https://usmodernist.org/index-pa.htm

(1949). Where to See Everyday Art. Everyday Art Quarterly, Winter 1949-1950 (No. 13), pp. 1-11. http://www.jstor.com/stable/4047161

About: Mission & History. Walker Art. https://walkerart.org/about/mission-history

Barnes, Edward Larrabee and Mildred S. Friedman. (1971). Walker Art Center 1971. Design Quarterly, (No. 9), pp. 1-22. http://www.jstor.com/stable/4047412

Blake, Peter. (1974). Brick-on-brick and white-on-white: the Walker Art Center may be the best modern museum in the U.S. Architecture plus volume 2 (Issue 4).

Bergdoll, Barry. (2009). I.M. Pei, Marcel Breuer, Edward Larrabee Barnes, and the New American Museum Design of the 1960s. Studies in the History of Art (Vol 73, Symposium Papers L: A Modernist Museum in Perspective: The East Building, National Gallery of Art), pp. 106-123. http://www.jstor.com/stable/42622475

Comazzi, John and Margaret Werry. (2008) The Walker Art Center + The Tyrone Guthrie Theater, Minneapolis: Two Views. Journal of Architectural Education (Vol. 61, No. 4, Performance/Architecture), pp. 131-135. http://www.jstor.com/stable/40480873

Dill, Emma. (2018, April 30). Walker Art Center. MNopedia. https://www.mnopedia.org/place/walker-art-center

Fischer, Mark (producer). (2013, May 26). Minneapolis Sculpture Garden [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.mnvideovault.org/index.php?id=24340&select_index=0&popup=yes#0.

Fox, Margalit. (2016, May 13). Martin Friedman, Whose Vision Shaped Walker Art Center, Dies at 90. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/14/arts/design/martin-friedman-whose-vision-shaped-walker-art-center-dies-at-90.html

Madison, Cathy. (2005). Walker Art Center: Art spaces. Scala Publishers Limited.

Ruddy, Martha. (1998, November). Daniel S. Defenbacher Papers, 1939-1951. [Biography, description]. WAC RG1 S1 (94.09.DO). https://s3.amazonaws.com/wac-imgix/cms/DSD_FA.pdf

Smith, David C. (2013, May 30). Minneapolis Sculpture Garden is 25. Retrieved from https://minneapolisparkhistory.com/2013/05/30/minneapolis-sculpture-garden-is-25/

Vuchetich, Jill. (2014, October 28). Ghost Building: Walker Galleries 1927. Walker Reader. https://walkerart.org/magazine/ghost-building-walker-galleries-1927

Vuchetich, Jill. (2014, October 8). Walker History: Shall We Take It? The Walker’s Founding Question. Walker Reader. https://walkerart.org/magazine/public-art-center-defenbacher

Yardley, Willian. (2014, September 9). Mildred Friedman, 85, Dies; Curator Elevated Design and Architecture. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/10/arts/design/mildred-friedman-design-curator-dies-at-85.html