Useful Art: Modern design of the Idea Houses at Walker Art Center

Idea House I and Idea House II. Photos Courtesy Hennepin County Public Library, Special Collections

Name of Building/Site:

Walker Art Center Idea House I and Idea House II

Building/Site Address:

725 Vineland Place

Minneapolis, MN 55403

Designation:

None apply

Summary:

The Idea House series was an experiment in Modern domestic design built by the Walker Art Center in the 1940s. These two exhibition homes were critical in the Walker’s project of introducing Modern design to Minneapolis. Idea House I (1941) and Idea House II (1947) illustrate the social context of postwar Minnesota and extend the museum experience beyond the walls of the Walker’s building, elevating domestic architecture and Modern design to an art form.

Author:

Mary Dahlman Begley is an architectural designer, researcher, and writer living in Minneapolis. December 2020.

WC: 2662

Construction Dates:

Idea House I: 1941 (Razed 1961)

Idea House II: 1947 (Razed 1969)

Architectural and Other Designer(s):

Idea House I: Malcolm Lein and Miriam Lein with Hilde Reiss, Curator of Design; David Defenbacher, director of Walker Art Center 1939-1951

Idea House II: William Friedman and Hilde Reiss, sponsored by Anderson Windows

Figure 1.

This 1947 aerial photo shows the newly completed Idea House II in its location west of Idea House I, completed in 1941.

[Aerial photograph] [cropped, edited] (1947). Minnesota Historical Aerial Photographs Online. http://geo.lib.umn.edu/minneapolis/1947/07-B-N.jpg

This 1947 aerial photo shows the newly completed Idea House II in its location west of Idea House I, completed in 1941.

[Aerial photograph] [cropped, edited] (1947). Minnesota Historical Aerial Photographs Online. http://geo.lib.umn.edu/minneapolis/1947/07-B-N.jpg

IDEA HOUSE I

Almost 80 years ago, on the ground adjacent to the current entrance to the Walker Art Center’s parking garage, an idea was built. Opened to the public in 1941, Idea House I was one of two fully functioning houses built on Vineland Place during that decade. (Figure 1) The Idea Houses extended the museum experience beyond the walls of the Walker’s building, and made spatial their agenda to bring art and people together. These domestic design exhibitions were critical in the Walker’s project of introducing Modern design to Minneapolis. The Idea House series sought to provide architectural ideas to an audience; the social context of the 1940s dictated the limits of the project’s accessibility.

In the early 1940s, the American domestic economy was still recovering from the Great Depression, which had prompted an extreme housing shortage. World War II raised the cost of residential construction from an estimated 40 cents to $1 per cubic foot, as building materials were diverted to the war effort. As WWII continued, practicality became a necessity for the art and design world. The straightforward, unadorned design of early Modernism flourished in part due to this cultural climate; the Walker Art Center’s vision to bring art and people together shared a similar practical mandate.

The Walker Art Gallery, founded in 1879 by lumber baron Thomas Barlow Walker, took a turn in 1938 when the Minnesota Art Council (MAC) contacted Daniel S. Defenbacher to begin the process of forming an alliance between public and private entities that would come to comprise the Walker Art Center. MAC, supported by the director of the Walker Art Gallery (a descendant of the baron), raised funds from Minneapolis citizens for a community art center. Defenbacher leveraged knowledge from his previous role with the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) for funding from the WPA to support art center staff.. The Walker Art Gallery donated their facility and collection to the effort, and the Walker Art Center was thus established in 1939, with Defenbacher as its first director.

|

Figure 2.

Idea House I had a single story, with clerestory windows at the living room. The designers placed emphasis on the interior, writing, “If a house is properly planned for living, a beautiful exterior is only a matter of applying competent designing ability.” [Idea House I - exterior] [photoprint]. Hennepin County Public Library, Special Collections Tumblr. https://hclib.tumblr.com/post/131828863133/the-walker-idea-houses-in-1941-the-walker-art |

Figure 3.

The kitchen of Idea House I featured stainless steel walls (easy to clean), fluorescent lighting, a variety of work areas, and the latest in cooling and cooking technology. [Idea House I - interior, kitchen] [photoprint]. Hennepin County Public Library, Special Collections Tumblr. https://hclib.tumblr.com/post/131828863133/the-walker-idea-houses-in-1941-the-walker-art |

Defenbacher focused exhibition efforts towards architecture and design, more specifically what he would come to call “useful art” - a principle of industrial design in the Modern era that posits design as the way an object is elevated from a product to an art form. The innovative, full-scale Idea House I was one such design experiment in useful art. St. Paul architects Malcolm and Miriam Lein were hired by Defenbacher to design the Idea House with a modest construction budget of $5000 (the final bill was $7000, $125k in 2020 figures, not inclusive of the cost of land and furnishings). This first iteration in the Idea House series used inexpensive and plain construction materials. (Figure 2) The design emphasized architectural technology, with a gleaming furnace, attic fan, laundry, and kitchen appliances, provided by local sponsors, in the showpiece house. (Figure 3) Intended to house a growing family of four, the flexibility of the space is denoted by using curtains as walls - including for the potential separation of two bedrooms. (Figure 4) This desire for flexibility is, also, ultimately, the design’s weakness; the lack of commitment to program or personal details left the house’s living spaces feeling anonymous. (Figure 5) The Idea House series was intended to provide exhibition-goers with concepts they could implement in their own homes - an innovative design brief that perhaps necessitated the degree of anonymity in the design, so the viewer may superimpose their own lives into the design. This participatory spectacle included, embedded within the design and concept, the potent symbol of the family; the single-family home is used as marketing for the importance, relevance, and usefulness of Modern design.

The architecture of domesticity is central to the Modernist project. Throughout the 20th century, the home was the site for the elaboration of Modernist architectural ideas, beginning in 1925 with Le Corbusier’s Pavilion de l’Esprit Nouveau in the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs. In the Pavilion - a model home built for exhibition in Paris - the Modern domestic design was on display, as well as plans for Le Corbusier’s utopian city, hung on the interior walls. The house was both backdrop and vehicle for Modernist architectural philosophy. The single family home served as a convenient scale that Modernist architects used to convey their ideas. Several exhibition homes were built, including George Fred Keck’s House of Tomorrow in the 1933 Chicago Century of Progress International Exposition, but Idea House I was the first to be built by a museum. Its opening in 1941 predated the popular Case Study House program in Los Angeles, begun in 1944 by Arts & Architecture magazine. The scale of the single family home was further convenient to demonstrate and popularize Modern design to a wider audience - the scale is familiar and necessary to everyday people. Importantly, the Walker’s Idea Houses were constructing a home for the present, not the future, and dealt with the intricate social, political, and design contexts of the era.

|

Figure 4.

To provide for maximum flexibility, Idea House I included “leather-covered, sound-proofed, accordian style screens” to separate the bedroom-study room into two. [Idea House I - interior, bedroom] [photoprint]. Hennepin County Public Library, Special Collections Tumblr. https://hclib.tumblr.com/post/131828863133/the-walker-idea-houses-in-1941-the-walker-art |

Figure 5.

The living-dining room of Idea House I also incorporated optional partitions, to separate multiple zones for maximum flexibility throughout the day. [Idea House I - interior, living] [photoprint]. Hennepin County Public Library, Special Collections Tumblr. https://hclib.tumblr.com/post/131828863133/the-walker-idea-houses-in-1941-the-walker-art |

EVERYDAY ART GALLERY

In 1944, Defenbacher appointed Hilde Reiss as the curator of the Walker’s new Everyday Art Gallery. Reiss shared Defenbacher’s commitment to “useful art” - Reiss was introduced to Modern design when she studied architecture under Walter Gropius at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany from 1930 to 1932. The Bauhaus was one of the most important players in the advent of Modernism, and known for a pedagogy that favored multi-disciplinary design with the goal to combine aesthetics with everyday functionality. Reiss moved to New York and taught at the Design Laboratory, a project of the WPA, where she met William Friedman, who would become her husband and colleague at the Walker Art Center. The couple were both hired by Defenbacher in 1944 (Friedman as Assistant Director in charge of Exhibitions, Reiss as Curator of the Everyday Art Gallery and Editor of Everyday Art Quarterly). Reiss’ training at the Bauhaus and work experience in both public and private sectors informed her design ethic, which she described as “straightforward and practical.” This sensibility translated well to Minneapolis, where the Everyday Art Gallery - through the display of consumer products - merged High Modernism with the quotidian.

The Everyday Art Gallery and Reiss’ involvement at the Walker illustrate two important conceptual themes of the Walker’s role in introducing Modernism to Minneapolis: design as an accessible art, and Minneapolis as a nexus for Modernist ideas. Everyday Art Gallery championed Modern design through educational exhibitions that sought to demystify the art of design. By displaying consumer products, the Gallery created a dual experience wherein the act of visiting the museum is likened to the act of going shopping, and the design of products is elevated to an art form. By showcasing chairs and teapots in the Modern style, the Walker reframed art as a designed object which could be purchased; the art is accessible, by design. This is a consumerist translation of Bauhaus principles, in which creative crafts are considered artful trades, through a designed revolution in the look and feel of domestic life. Furthermore, Reiss’ education at the Bauhaus, along with Reiss’ and Friedman’s experience working at prestige firms in New York, brought fresh ideas to Minneapolis, a Midwestern city otherwise removed from European High Modernism. Later in the era, designers Martin and Mildred Friedman (no relation to William) would bring Midcentury Modernism to Minneapolis from California, via their education and acquaintance with West Coast modernists such as George Nelson, and the Eameses. Minneapolis was thus a meeting ground for different strains of Modern design, and the Walker served as a nexus for popularizing Modernism.

|

Figure 6. Idea House II was a more ambitious iteration of the prior. This split level home used gently sloping roofs and Windowalls, rather than the flat roof and glass wall typical of High Modernism, in attempt to prove the value of Modern design. [The Exterior of the Idea House II Exhibit at the Walker Art Center] [photoprint]. Hennepin County Public Library, Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/MplsPhotos/id/45061/rec/1 |

IDEA HOUSE II

By 1946, the War was over. As military men returned home, the anticipation of a leisurely peacetime American lifestyle was high. The 1944 Servicemen's Readjustment Act provided veterans with low interest, zero down payment home loans, encouraging the construction of new suburban homes. This legislation, combined with a booming market for consumer and construction products, thanks to wartime technical innovations, accelerated the traditional aspiration of home ownership. However, the Act was administered by individual state governments - one of the many factors that spurred the Great Migration, the relocation of millions of Black Americans from the Jim Crow South to the urban North. In spite of the alluring promise of home ownership, discriminatory lending policies and neighborhood redlining was prevalent in Northern Cities. The Twin Cities were growing, but housing options for Americans of color were not.

In September 1947, when the second of the Walker’s Idea Houses opened, the country was still one year away from the 1948 Shelley v. Kramer case that made racial housing covenants unenforceable, and six years before the Minnesota Legislature explicitly prohibited the use of racial restrictions in deed in 1953. Despite these legislative efforts, discriminatory housing practices were not outlawed until the Fair Housing Act of 1968. It is through this societal context that the “useful art” of the Idea House series must be evaluated. The aim of the Idea House series to offer visitors ideas to propagate their own domestic bliss implicitly left out large portions of the population. The design intent, as articulated by curator Andrew Blauvet in the Walker’s 2000 exhibition revisiting the Idea Houses, was to draw on the rhetoric of Yankee ingenuity, designing with a practical utility that appealed to American aspirations of freedom and individuality. The motivation of “useful art” in the Idea House series, to elevate domestic life to an art form through good design, tacitly avoids the social context of race; the inverse, whereby through acceptance and education of design, art is democratized and made available to a majority of the population, is explicitly false in this context. While the Idea House series publicized Modernism in Minneapolis, the avenues for adherence to a Modernist domestic lifestyle were limited for many Minneapolitians.

Idea House II was a more ambitious iteration of the prior in every way. Designed by William Friedman and Hilde Reiss, the design brief of this second Idea House was vastly different from the first, with a focus on growing families, rather than maximum affordability. (Figure 6) In 1947, GIs were returning home from World War II to begin the baby boom; the implied resident of the both Idea Houses are a heterosexual couple with young children, a prescriptive ideal made spatial in the design. The population of Minneapolis was growing - between 1940 and 1950, Minneapolis gained 29,000 citizens, an increase of 6%. Affordability was nevertheless still a goal, as construction costs remained high after the war. Idea House II used modest finishes and innovative design solutions meant to use space efficiently. Expanded partnerships with brands for architectural technologies and products subsidized the cost of construction for the Walker Art Center, but the price tag was more than $20,000 (not including land and furnishings) - a hefty sum for families of the era, and more than 150% the cost of Idea House I.

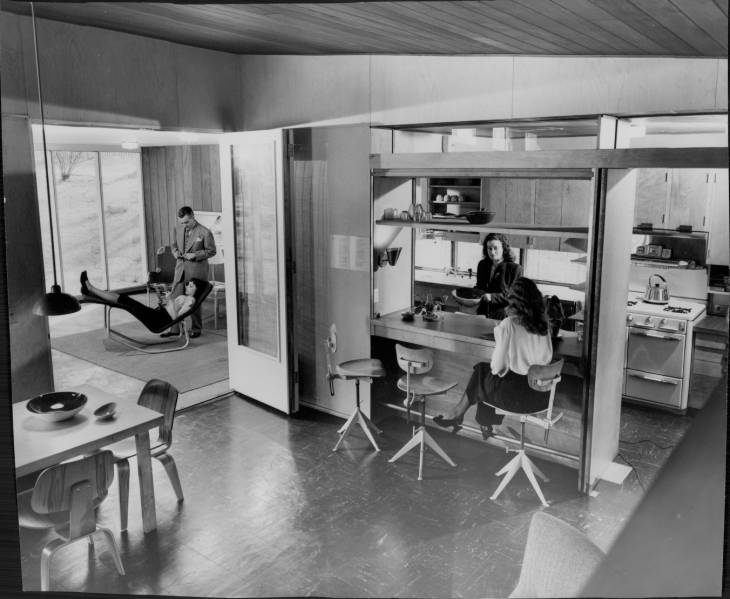

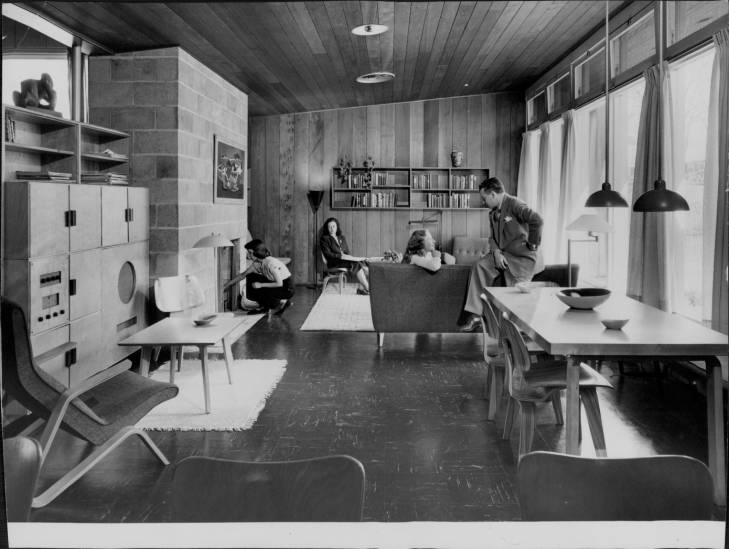

Idea House II is designed into the natural slope of the plot, with an entry at ground level, below the main mass of the house. The upper levels are split into two wings, both oriented to face the garden in the south. In the west wing, a 4-in-1 living area combines programs; the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune described it in 1947 as including an “all purpose family work table, dining-recreation porch, handy kitchen and breakfast bar.” (Figure 7) The kitchen and screened-in porch are integral to the living area, yet isolatable through innovative enclosures. In the east wing are the living quarters. The “Children’s Apartment” has a rubber-tiled common play area adjacent to two individual sleeping alcoves, also isolatable through enclosure. The parent’s bedroom is large and includes a fireplace and a sliding plastic door. The bathroom is split into two parts, a standard toilet in the smaller room and a prefabricated Stand-Fab single-piece bathroom unit in the larger room. These experimental design ideas resulted in oddly shaped rooms, flowing one into the next, an extraordinary interior when compared to the homes being built elsewhere in Minneapolis - a residential landscape dominated by bungalows divided into small rooms on the interior. The house’s interior furnishings straddled a tension in Modern design: the utility and practicality of built-in storage, heavy in contrast to lightweight, portable furniture pieces. (Figure 8) Built-in pieces, such as a Storagewall (pioneered by George Nelson), a two-way breakfast bar, and birch cabinetry in the kitchen, maximized storage space and incorporated several types of wood finish to the home. The furniture included designs by architects, including Charles Eames-designed molded plywood chairs, table and stools by Alvar Aalto, a slat bench by George Nelson, and light fixture by Harry Weese. At the time, Modernist furniture was trickling into mass production, and with the exception of the built-in pieces, all furniture displayed in Idea House II was available for purchase from manufacturers listed in the brochure.

|

Figure 7.

The west wing combined program zones into a free-flowing space, yet allowed for isolation with innovative doors at every opening. Eames plywood chairs were among many architect-designed Modern furnitures in the home. [The Kitchen and Living Room of the Idea House II Exhibit at the Walker Art Center] [photoprint]. Hennepin County Public Library, Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/MplsPhotos/id/45273/rec/3 |

Figure 8.

Visitors to the museum in the summer of 1947 could tour the space, except during promotional periods when various institutions sponsored families or groups to live in the home for a period, to record their reactions. Later, the house became residency for Walker staff. [The Living and Dining Rooms of the Idea House II Exhibit at the Walker Art Center] [photoprint]. Hennepin County Public Library, Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/MplsPhotos/id/45180/rec/4 |

The list of design features in Idea House II included technical innovations, fashionable furniture, and, of course, experimental architectural ideas. The house was thus marketed like many consumer products of the day: with a list of yearly features, sold anew each year. But like the latest gizmo, some design features would not stand the test of time. After their stint as exhibitions, the Idea Houses became home for Walker staff. Eleanor Arnason, who lived as a young girl in the home with her family in the 1950s, during H. Harvard Arnason’s tenure as the Director of the Walker, noted in 2000 that it was “easier to talk about what was wrong with the house than what was right with the house.” Privacy was an ongoing issue in the free-flowing design, particularly as the children aged out of the child-sized alcoves. The Arnasons eventually turned the screened-in porch to a bedroom for Eleanor; it was a cold room, due in part to the slab concrete poured directly onto the ground with no lower level to buffer the frozen ground. During the Cold War’s Red Scare, with rising fear of nuclear war, there was no basement in which the family could shelter during drills. The extraordinary sunlight in the house backfired at night, when the experience of living in the home was like a fishbowl, particularly when events at the adjacent Parade Stadium brought visitors to the area after dark. These features, with their advantages and drawbacks, were talking points for visitors. The medium of the Idea House series as an exhibition home invited criticism from viewers in a way that art exhibited inside the museum did not. With art, particularly Modern art, the average visitor may not feel confident in their opinions or criticism; everyone who saw the Idea Houses were experts in living in a home, and could evaluate the merits of the design. This may be the ultimate feature in the Idea Houses: the evaluation, in the eyes of the visitors, of the art’s usefulness.

Idea Houses I and II stood on Vineland Place until the construction of the Guthrie Theater, designed by Ralph Rapson, caused the demolition of Idea House I in 1961. In 1969, an expansion of the Guthrie caused the demotion of Idea House II and the end of an era in the Walker’s history with Modernism. The project of Defenbacher, Reiss, the Everyday Art Gallery and the Idea House series to prosthelytize Modern Design was effective in the City: curator Blauvet cited the designs of University Grove, a Modernist residential enclave in Minneapolis, as evidence of the Idea House’s influence. This influence was ultimately inaccessible for many Americans; the design of the Idea House series prescribed an exclusionary vision of the family home, and the success of “useful art” must be evaluated in social context of the era. With the construction of Edward Larrabee Barnes building for the Walker in 1971, the institution was positioned towards the contemporary era. The Late Modernist design towers over the footprint of where the Idea Houses once stood, now just a memory of the Walker’s first built foray into Modernism, and a useful case study of domestic design in the social context of postwar Minnesota.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Carefree Living with Automatic GAS Equipment” (advertisement) in Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, 28 September 1947, p. 8.

“Idea House” (advertisement) in Minneapolis Tribune and Star Journal, 1 June 1941.

“Idea House II” in Minnesota By Design, Walker Art Center online archives, https://walkerart.org/minnesotabydesign/objects/idea-house-ii

“Idea House II” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, 28 September 1947.

“‘Idea House’ Built by Art Museum Serves as Guide to Future Home Owners.” The Christian Science Monitor, 12 June 1941.

Adams, Cedric. “In This Corner.” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, 21 September 1947, p. 6.

El-Hai, Jack. Lost Minnesota : Stories of Vanished Places. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

Hatler, Carrie. “Walker Art Center’s Idea House.” Forgotten Minnesota. 11 March 2011. https://forgottenminnesota.com/blog/2011/03/walker-art-centers-idea-house

“Minneapolis Housewives Like It Because: It Looks Easy to Keep Clean” The Washington Post, 28 December 1947, p. C4.

Premack, Frank. “Curtain Falls on Idea House to Make Way for Theater.” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, 19 November 1961, p. 3.

Walker Art Center, and Andrew Blauvelt. Ideas for Modern Living : The Idea House Project / Everyday Art Gallery. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2000.

Winton, Alexandra Griffith. “‘A Man’s House is his Art’: The Walker Art Center’s ‘Idea House’ project and the Marketing of Domestic Design 1941-1947.” Journal of Design History, vol. 17, No. 4 (2004), p. 377-396. http://www.jstor.com/stable/3527001

Wright, Bruce N. “Visions of a New World? The Walker Art Center Idea House II.” Hennepin History, vol. 52, No. 3 (Summer 1993), p. 16-38. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll13/id/4230

“Carefree Living with Automatic GAS Equipment” (advertisement) in Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, 28 September 1947, p. 8.

“Idea House” (advertisement) in Minneapolis Tribune and Star Journal, 1 June 1941.

“Idea House II” in Minnesota By Design, Walker Art Center online archives, https://walkerart.org/minnesotabydesign/objects/idea-house-ii

“Idea House II” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, 28 September 1947.

“‘Idea House’ Built by Art Museum Serves as Guide to Future Home Owners.” The Christian Science Monitor, 12 June 1941.

Adams, Cedric. “In This Corner.” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, 21 September 1947, p. 6.

El-Hai, Jack. Lost Minnesota : Stories of Vanished Places. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

Hatler, Carrie. “Walker Art Center’s Idea House.” Forgotten Minnesota. 11 March 2011. https://forgottenminnesota.com/blog/2011/03/walker-art-centers-idea-house

“Minneapolis Housewives Like It Because: It Looks Easy to Keep Clean” The Washington Post, 28 December 1947, p. C4.

Premack, Frank. “Curtain Falls on Idea House to Make Way for Theater.” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, 19 November 1961, p. 3.

Walker Art Center, and Andrew Blauvelt. Ideas for Modern Living : The Idea House Project / Everyday Art Gallery. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2000.

Winton, Alexandra Griffith. “‘A Man’s House is his Art’: The Walker Art Center’s ‘Idea House’ project and the Marketing of Domestic Design 1941-1947.” Journal of Design History, vol. 17, No. 4 (2004), p. 377-396. http://www.jstor.com/stable/3527001

Wright, Bruce N. “Visions of a New World? The Walker Art Center Idea House II.” Hennepin History, vol. 52, No. 3 (Summer 1993), p. 16-38. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll13/id/4230