Cabin Culture: Five Modernist Cabins

Ralph Rapson's Glass Cube. Amery, Wisconsin. Photo Courtesy Corey Gaffer.

Author:

Mary Dahlman Begley is an architectural designer, researcher, and writer living in Chicago. January, 2024.

WC: 2359

INTRODUCTION

Origins of Cabin Culture

For the last hundred years, “cabin culture” has grown into a dominant trait of Minnesotan identity. Many native Minnesotans can reminisce about childhood trips “up north” and conjure pleasant images of pine-ringed lakes and a cozy cabin. While the phenomenon of owning or visiting a cabin in the Upper Midwest is widespread, it did not happen by accident. Cabin culture is the byproduct of industrial pursuits, the goal of postwar regional boosters, and, every so often, the precise conditions for exceptional modern architecture.

In 1940, Governor Harold Stassen described northern Minnesota as “crown[ed with] thousands of jewel-like lakes, fringed with beautiful forest lands, alive with game and fish, ribboned by thousands of miles of modern highways, and dotted with hundreds of cabins and campsites.” This verdant area, along with similarly beautiful and adjacent areas in Wisconsin and Michigan, roughly form the region known as “up north” to Midwesterners. Throughout the industrial era, cabins existed, whether they were hunting shacks or outposts for family fun.

Mary Dahlman Begley is an architectural designer, researcher, and writer living in Chicago. January, 2024.

WC: 2359

INTRODUCTION

Origins of Cabin Culture

For the last hundred years, “cabin culture” has grown into a dominant trait of Minnesotan identity. Many native Minnesotans can reminisce about childhood trips “up north” and conjure pleasant images of pine-ringed lakes and a cozy cabin. While the phenomenon of owning or visiting a cabin in the Upper Midwest is widespread, it did not happen by accident. Cabin culture is the byproduct of industrial pursuits, the goal of postwar regional boosters, and, every so often, the precise conditions for exceptional modern architecture.

In 1940, Governor Harold Stassen described northern Minnesota as “crown[ed with] thousands of jewel-like lakes, fringed with beautiful forest lands, alive with game and fish, ribboned by thousands of miles of modern highways, and dotted with hundreds of cabins and campsites.” This verdant area, along with similarly beautiful and adjacent areas in Wisconsin and Michigan, roughly form the region known as “up north” to Midwesterners. Throughout the industrial era, cabins existed, whether they were hunting shacks or outposts for family fun.

North Woods

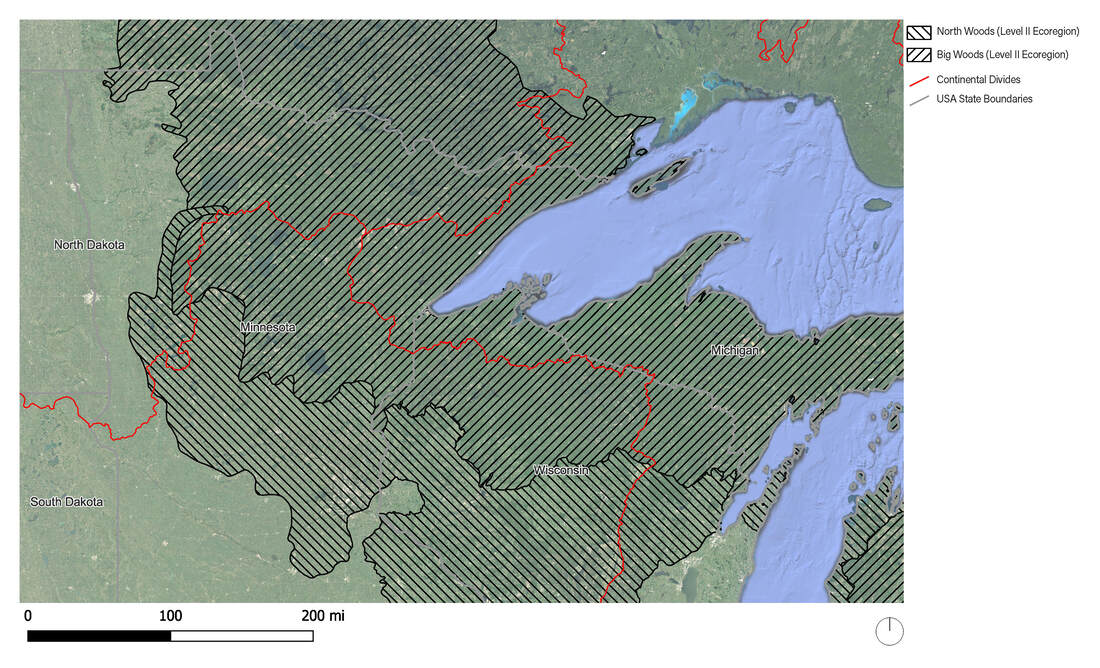

The Laurentian and Saint Lawrence continental divides arc through Minnesota and Wisconsin, marking the watersheds for the thousands of lakes and rivers that connect the forested ecoregion known as the Laurentian Mixed Forest Province, or, the North Woods. The edges of the Canadian Shield are the geologic trademark of the North Woods ecoregion, with exposed volcanic rock visible throughout. This area is the nexus of cabin culture for the midwest. [Image1]

Cabin ownership in this area is varied, but further to the south in the Big Woods ecoregion, along the border of Minnesota and Wisconsin, many cottages are owned by individuals from the Twin Cities. Proximity to larger cities informs patterns of cabin ownership; historic social and political factors inform patterns of settlement in this region.

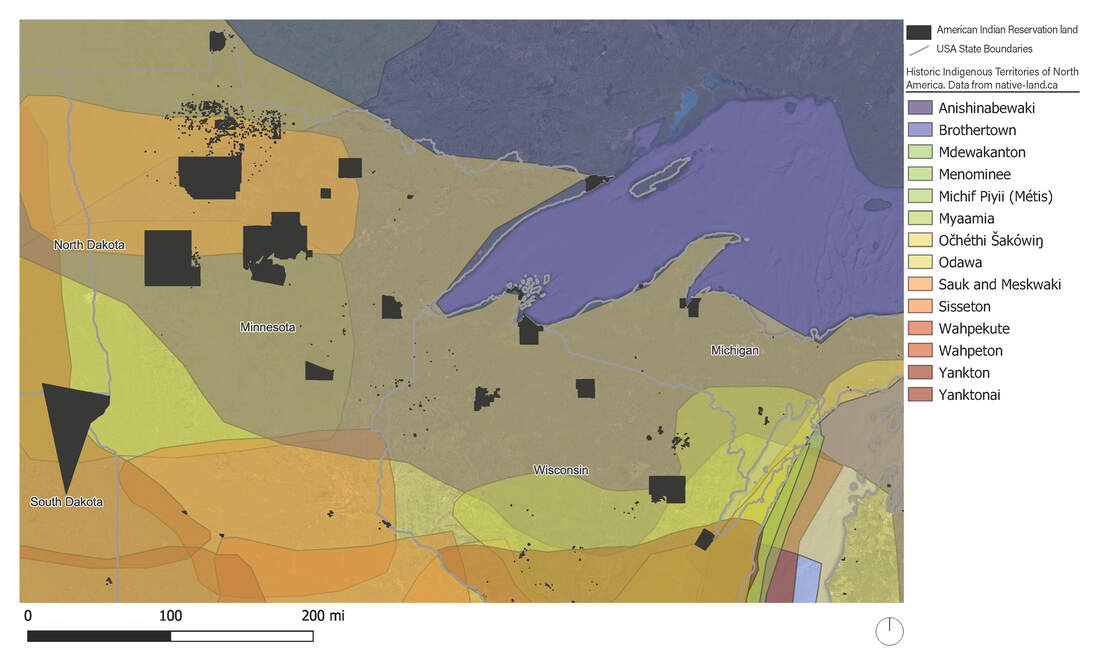

The North Woods and Big Woods ecoregions are the ancestral homeland of Oceti Sakowin, Anishinaabe, and other peoples, who lived with the land until the United States inflicted settler colonial policies in the nineteenth century. The Dawes Act of 1887 reorganization of the territory formalized the possession of this land into the United States. Large swaths of land changed hands to Euro-American settlers, ushering native populations into reservations and gradually reducing their territory through further treaty agreements. [Image 2]

The Laurentian and Saint Lawrence continental divides arc through Minnesota and Wisconsin, marking the watersheds for the thousands of lakes and rivers that connect the forested ecoregion known as the Laurentian Mixed Forest Province, or, the North Woods. The edges of the Canadian Shield are the geologic trademark of the North Woods ecoregion, with exposed volcanic rock visible throughout. This area is the nexus of cabin culture for the midwest. [Image1]

Cabin ownership in this area is varied, but further to the south in the Big Woods ecoregion, along the border of Minnesota and Wisconsin, many cottages are owned by individuals from the Twin Cities. Proximity to larger cities informs patterns of cabin ownership; historic social and political factors inform patterns of settlement in this region.

The North Woods and Big Woods ecoregions are the ancestral homeland of Oceti Sakowin, Anishinaabe, and other peoples, who lived with the land until the United States inflicted settler colonial policies in the nineteenth century. The Dawes Act of 1887 reorganization of the territory formalized the possession of this land into the United States. Large swaths of land changed hands to Euro-American settlers, ushering native populations into reservations and gradually reducing their territory through further treaty agreements. [Image 2]

|

Image 1.

The upper midwest region is defined by geography, geology, and ecoregions that converge for a dramatic effect in the beautiful “up north” area. Map of Level II ecoregions, continental divides, USA state boundaries. Data from USGS, 2023. Courtesy Mary D. Begley. |

Image 2.

USA policies towards indigenous peoples in North America forced relocation and made land available for settler speculation and use. Map of American Indian Reservations (2018 data from Dept of Interior), historic indigenous territories of North America (data from native-land.ca), USA state boundaries. Data from USGS, 2023. Courtesy Mary D. Begley. |

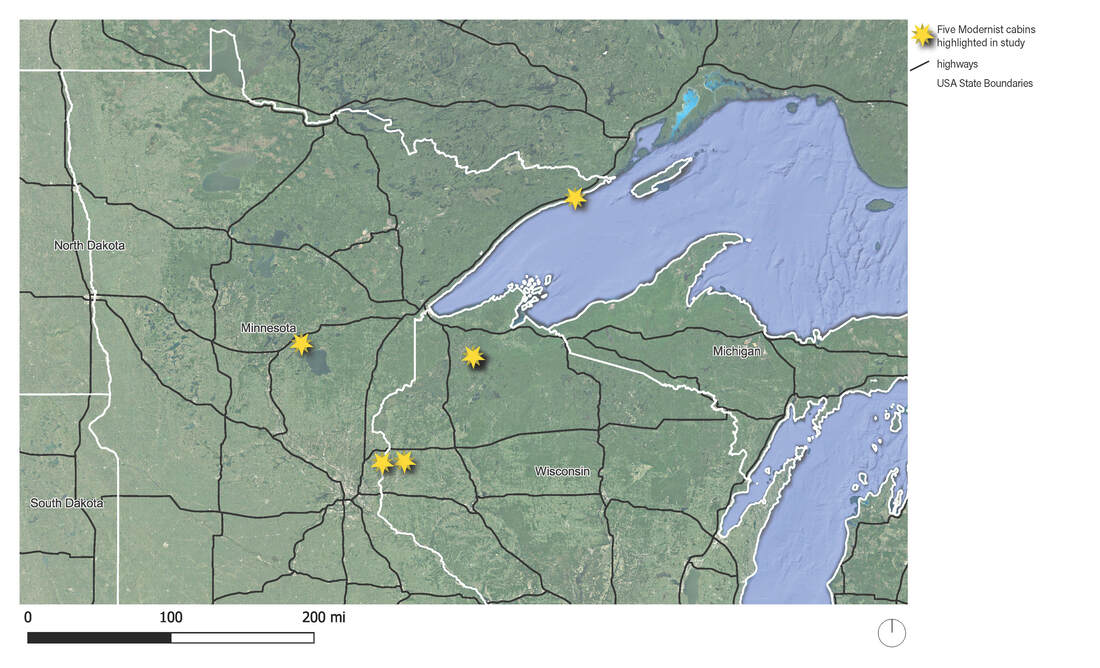

Image 3.

Increased transportation options in the 20th century made areas near larger cities popular for cabins. Map of Level II ecoregions, continental divides, USA state boundaries. Data from USGS, 2023. Courtesy Mary D. Begley. |

Some of this land was made available to settlers for homesteading purposes, and some land was turned over to industrial pursuits as technological developments created growing markets for lumber and coal. With forests open to wide-scale harvesting, the white pine lumber industry marched through the region from east to west, arriving to the north shores of Lake Superior. The cities of Duluth, Grand Portage, and Thunder Bay made the transition from historic fur trading posts to their next iterations as industrial cities. In 1870, Duluth was selected as a railhead and became one of the world’s leading grain shipping ports by 1885. Connecting land and water opened more routes for shipping goods, which facilitated a growing market for consumer products, and effectively changed the landscape of the Upper Midwest during the industrial era. By the 1920s, the northern parts of Wisconsin and Michigan and the northeastern region of Minnesota faced thinning forests and were no longer viable for lumber speculation.

What to do with the deforested land, now unsightly and unuseful? Due to the long winters, redeveloping the land for farming was unevenly successful across the region. Some areas, such as Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and Minnesota’s Iron Range, found success in mining mineral resources. In 1919, regional leaders from Minnesota and Michigan met in Saint Paul to discuss what would become the first cooperative effort to emphasize the North Woods as a destination for tourism. Cutover country was to become vacationland. Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota engaged in various tactics to advertise their lush landscapes, competing with neighboring states for the eyes and dollars of the region’s growing number of tourists. Just as other natural resources, scenery was viewed as an asset to exploit, and tourism as a crop worth cultivating. In Minnesota, the expanding Trunk Highway system opened access to new areas, and the number of resorts in the state grew from a few hundred in the 19th century to 1,400 in the 1920s. The ramifications of the upper midwest’s changing economy from industry-dominant to leisure has lasting effects and is still visible in the built environment. Railroads, both extant and derelict, crisscross the landscape; highways cut through cliffs and wind around hills; vestiges of mines and quarries, now open as museums and natural areas, stipple the geology; historic cabins tell architectural and societal stories of the past. [Image 3]

Cabin, Cottage, or Lake Home?

Residences dotting the upper midwest may be called cabins, cottages, lake homes, lakeshore cottages, summer houses, or any number of varying monikers that describe a home-away-from-home. To sort through these names, consider the building’s temporal use—cabin and cottage have seasonal connotations and are visited mostly in the summer, while lake home suggests year-round occupancy. The location of the building may also inform what it is called. Cabins are more common in mountainous locations, while cottages are more likely to be near bodies of water. However, the location is not the absolute determinant for what a building is called. Twin Cities architect and cabin expert Dale Mulfinger wrote that “[the] same building situated in, say, northern Wisconsin may be called a cottage if the owner lives in Milwaukee and a cabin if the owner comes from Minneapolis.”

Residences dotting the upper midwest may be called cabins, cottages, lake homes, lakeshore cottages, summer houses, or any number of varying monikers that describe a home-away-from-home. To sort through these names, consider the building’s temporal use—cabin and cottage have seasonal connotations and are visited mostly in the summer, while lake home suggests year-round occupancy. The location of the building may also inform what it is called. Cabins are more common in mountainous locations, while cottages are more likely to be near bodies of water. However, the location is not the absolute determinant for what a building is called. Twin Cities architect and cabin expert Dale Mulfinger wrote that “[the] same building situated in, say, northern Wisconsin may be called a cottage if the owner lives in Milwaukee and a cabin if the owner comes from Minneapolis.”

|

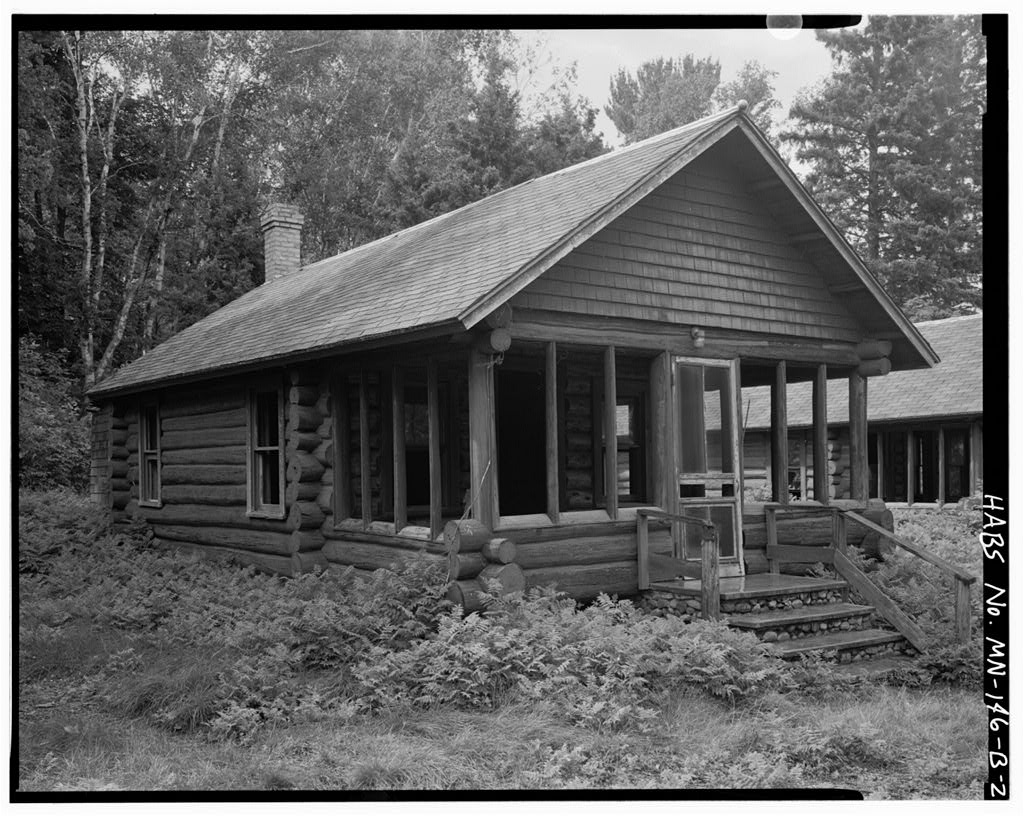

The architecture of these buildings can be as idiosyncratic as the moniker. The majority of cabins are not designed by architects, and many are self-built or constructed by amateurs. There is no common architectural style of cabins. Some use rustic materials or take inspiration from their surroundings in form or ornament. In Minnesota, many buildings at National and State Parks were constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and use log or stone construction. [Image 4]

A number of these Park buildings were admitted to the National Register of Historic Places as “Rustic Style Historic Resources,” noted for their architectural significance by association with the social, political, and economic impacts of the Great Depression. These park cabins are rustic in style and in nature, with primitive facilities and woodfire stoves for cooking and heating. Contemporary cabins typically include indoor plumbing, but may still take on rustic styling to some degree. Use of unadulterated materials is common for architects of the modernist movement, but modernist architects preferred wood and stone shaped by industrial machinery, rather than rustic style hand-hewn logs and lake-washed stone available to cabin builders. The tension of modern machinery and rustic natural context, informs the modernist notion of cabin architecture. This study highlights five modernist projects that represent different ideas in cabin culture. The modernist cabin provides access to nature, and, through historic context, demonstrates ideas about gathering in community and changing ideas about the environment. This study traces modernism through cabin architecture to highlight five locations from the Docomomo US/MN Minnesota Modern Registry. |

Image 4.

The Joyce Cabin, built 1917, in Chippewa National Forest is an example of both the rustic style associated with early cabins and the newly-available opportunity to build on federal lands during the first decades of the 20th century. Historic American Buildings Survey, Creator. “Joyce Estate, Joyce Cabin.” Photograph. Minnesota Itasca County, 1933. https://www.loc.gov/item/mn0476/ |

NANIBOUJOU CLUB LODGE; 1928-1929

In 1928, a group of wealthy businessmen called the Naniboujou Holding Company in Duluth broke ground on the north shore of Lake Superior for the construction of a grand lodge. The region had recently become accessible through the construction of what is now US Highway 61. In 1918, following the conclusion of WWI, the State of Minnesota tasked the Ten Thousand Lakes of Minnesota Association with the goal of boosting tourism in the state. The following decade marked a period of competition between Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan, each of which tried out new slogans, advertising, guide- and pamphlet-making in order to attract more tourists. A citizen suggestion prompted Minnesota to emblazon their license plate with “Land of Ten Thousand Lakes” in 1926, a tactic for luring motorists to the region. Attempting to capitalize on this momentum, the Naniboujou Holding Company employed Duluth architects Holstead and Sullivan to design a 150-room lodge with cabins, a swimming pool, a tennis court, and a golf course on the 3,000 acre lot along 5,200 feet of Lake Superior shoreline. [Image 5] The lodge was exclusive—the members' only access appealed to celebrities including Jack Dempsey and Babe Ruth, who signed on but likely never made it for a visit.

In 1928, a group of wealthy businessmen called the Naniboujou Holding Company in Duluth broke ground on the north shore of Lake Superior for the construction of a grand lodge. The region had recently become accessible through the construction of what is now US Highway 61. In 1918, following the conclusion of WWI, the State of Minnesota tasked the Ten Thousand Lakes of Minnesota Association with the goal of boosting tourism in the state. The following decade marked a period of competition between Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan, each of which tried out new slogans, advertising, guide- and pamphlet-making in order to attract more tourists. A citizen suggestion prompted Minnesota to emblazon their license plate with “Land of Ten Thousand Lakes” in 1926, a tactic for luring motorists to the region. Attempting to capitalize on this momentum, the Naniboujou Holding Company employed Duluth architects Holstead and Sullivan to design a 150-room lodge with cabins, a swimming pool, a tennis court, and a golf course on the 3,000 acre lot along 5,200 feet of Lake Superior shoreline. [Image 5] The lodge was exclusive—the members' only access appealed to celebrities including Jack Dempsey and Babe Ruth, who signed on but likely never made it for a visit.

Image 5.

Architects Holstead & Sullivan produced this scheme for Naniboujou Club Lodge in 1927. The original design included 150 rooms, cabins, a swimming pool, a tennis court, and a golf course; only the dining room and 28 guest rooms were ever completed.

Nelson, Charles W. and Mark e. Haidet. “Naniboujou Club Lodge.” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form. Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, May 5, 1982.

Architects Holstead & Sullivan produced this scheme for Naniboujou Club Lodge in 1927. The original design included 150 rooms, cabins, a swimming pool, a tennis court, and a golf course; only the dining room and 28 guest rooms were ever completed.

Nelson, Charles W. and Mark e. Haidet. “Naniboujou Club Lodge.” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form. Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, May 5, 1982.

The Naniboujou Holding Club rushed to open the doors of the Lodge, the first building constructed on the site. It opened on July 9, 1929, shortly before the stock market crashed. The Lodge as it was planned was never fully built. Throughout the Great Depression and WWII, the Lodge was intermittently closed, but some visitors did make it there. Arriving first by boat, then by train, guests in the first few decades of the Naniboujou’s operation would stay for several weeks at a time. Some visitors came to the North Woods for preventative health care, believing that the fresh air would ward off contemporary diseases like diphtheria and polio. Today, visitors come by car to Naniboujou for a stay in one of its 28 guest rooms. The Lodge has three wings arranged in a C-shape, angled toward where the Brule River meets Lake Superior. The exterior is clad in shingles with cheerily painted bright red trim on all pointed arch windows. The roof curls over the walls in a gambrel-inspired form, subsuming the upper level into a single mass, like an elongated, oversized barn. [Image 6, Image 7] Entering at the turreted portal to the dining room is stepping right into the heart of Naniboujou. Awash with kaleidoscopic color, the dining room is painted from floor to domed ceiling with geometric designs, covering every surface except the giant stone fireplace. [Image 8, Image 9] Tim Ramey, the Lodge’s owner since 1985 and manager since 1980, notes that the colors of the painted room have not faded over time because the room gets no direct sunlight. Over the years the guest rooms have been updated. A solarium was added in 1983, but the dining room paintings and oversize stone fireplace remain intact, untouched since their completion. [Image 10, Image 11] The dining room is the focal point, with its elaborate ornamentation marking the central nexus of activity for the building. In form, program, and style, the Naniboujou has an emphasis on collective experience, gathering, and making shared memories.

|

Image 6.

The Lodge has three wings arranged in a C-shape, angled toward where the Brule River meets Lake Superior. Photo Courtesy Mary D. Begley. |

Image 7.

The exterior of Naniboujou lodge takes inspiration from shingle-style architecture, which celebrates colonial American forms and typically uses the same shingle material for walls and roof. Photo Courtesy Mary D. Begley. |

Image 8.

The dining room at Naniboujou Lodge is open to lodge guests and the public. Photo Courtesy Mary D. Begley. |

The colorful designs of the dining room at Naniboujou invoke the Art Deco tradition of mixing local cultural themes in streamlined, exaggerated visual art. Art Deco was a middle ground between radical modernist architects that rejected tradition and the traditionalist urge to maintain classical order. By blending ancient imagery with futuristic streamlined geometric patterns, Art Deco practitioners reconciled the past and future in the interwar period—a volatile time, both politically and in the world of design. Naniboujou is the name for the Cree god of joy and trickery. In Thunder Bay, Nanabijou is the Ojibwe name for the Sleeping Giant, a rock formation in the bay. The paintings in the Lodge dining room, performed in-situ by French-Canadian painter Antoine Gouffe, have visual similarities to Cree motifs. This northern shore of Lake Superior has been a great mixing place for indigenous people of North America, white visitors (whether settlers or tourists), and many others. It’s unclear why the Duluth businessmen chose the name Naniboujou for their venture - a name from much further north - just as it is unclear how Antoine Gouffe derived inspiration for the dining room painting. The paintings, in their design and in their sheer existence, demonstrate the colonial forces that disrupted the ancestral homeland of indigenous individuals. As a historic artifact, the architecture and decoration of the Lodge represent early twentieth century ideas about tourism in the North Woods as a destination for relaxation, gathering, and communing with nature in social conviviality.

|

Image 9.

Dining room interior of Naniboujou as featured in a 1973 postcard. The paintings and decorations are the same today, with minimal fading thanks to a lack of direct sunlight into the room. Nelson, Charles W. and Mark e. Haidet. “Naniboujou Club Lodge.” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form. Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, May 5, 1982. Image 11.

The chandeliers of the dining room are made of paper and are original to the 1929 Lodge opening. Owner Tim Ramey speculates that the planned chandeliers did not arrive in time for the hurried opening, and proprietors created these paper fixtures as a substitute. Photo Courtesy Tim Ramey. |

Image 10.

The massive stone fireplace is constructed of water-washed stones arranged in flower petal patterns. The 12’ tall fireplace weighs in at an estimated 200 tons. Photo Courtesy Tim Ramey. |

New Deal for the North Woods

Naniboujou Club Lodge was never built out to its full, 150-room extent, and members dropped out due to the Great Depression. The North Woods region did find some momentum in the interwar period, as federal funding for New Deal programming built up the tourist industry and promised a shot at recovery. Across the country new roads, conservation projects, and the Federal Writers Project’s American Guides promoted travel as a means to bolster the nation during and after the Great Depression. Minnesota was the first of the North Woods states to establish a state park system, complete with CCC-built park facilities and cabins. Narratives about tourism as a saving grace for post-industrial landscapes in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan united leisure with the idea of mitigating industry’s impact on the land through conservation efforts. Tourism boards in the region sought to protect and package nature to meet changing consumer trends, casting the outdoors as a source of leisure, relaxation, and gathering, rather than a place of labor and extraction. As WWII dawned, cabins persisted as an economical and virtuous vacation choice for young families, although wartime shortage would stall production and construction for many years to come.

Naniboujou Club Lodge was never built out to its full, 150-room extent, and members dropped out due to the Great Depression. The North Woods region did find some momentum in the interwar period, as federal funding for New Deal programming built up the tourist industry and promised a shot at recovery. Across the country new roads, conservation projects, and the Federal Writers Project’s American Guides promoted travel as a means to bolster the nation during and after the Great Depression. Minnesota was the first of the North Woods states to establish a state park system, complete with CCC-built park facilities and cabins. Narratives about tourism as a saving grace for post-industrial landscapes in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan united leisure with the idea of mitigating industry’s impact on the land through conservation efforts. Tourism boards in the region sought to protect and package nature to meet changing consumer trends, casting the outdoors as a source of leisure, relaxation, and gathering, rather than a place of labor and extraction. As WWII dawned, cabins persisted as an economical and virtuous vacation choice for young families, although wartime shortage would stall production and construction for many years to come.

SKYWATER; 1941, 1961

Interwar years and the Great Depression were years of global cultural change and exchange, including the introduction of modernism to the US and, by way of a young couple, to Minnesota. Close and Scheu, Architects, were renamed to Elizabeth and Winston Close, Architects, upon the occasion of Elizabeth and Winston’s marriage in 1939. Elizabeth, known as Lisl, was born in 1912 to Austrian intelligentsia. She grew up steeped in early modernism and the social housing agenda of Red Vienna. Lisl’s family commissioned a modernist house designed by Adolf Loos, frequently hosted members of the Social Democrats for salons and parties, and introduced her to the potential of housing with a social agenda. In 1932 Lisl fled Austria and enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she met Winston (known as Win). With their newly attained degrees and a shared interest in modernist housing, the two moved to Minnesota and began their practice. Lisl was the first woman to be a registered architect in Minnesota, and formed the first distinctively modern architectural practice in Minnesota with Win. Despite a stint during WWII when the office was closed, the pair produced a wartime cottage design that married modernism to the rustic language of cabin culture.

Joseph and Dagmar Beach lived near the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, where Joseph was the head of the English Department. They hired the Close architecture duo to design a low-budget cabin on a hillside site in Osceola, Wisconsin. With no access road, no water, and no electricity, the site for the cabin was rustic and challenging. Cut into the ravine above the St. Croix river, Dagmar described the site as midway between sky and water. The Closes designed “Skywater” with three of the four walls embedded into the earth. From the path leading in, the structure’s sod roof, more than two feet thick with soil, and stone walls, studded with rocks picked up around the site, are invisible in the leafy forest. [Image 12] Both of these construction techniques are traditional, not modern. Lisl cited the inspiration for the sod roof, saying in 1968, “The Finns have been using sod roofs for years and the result is a natural air conditioner.” The fourth wall, facing the river, is made entirely of glass, with a cantilevered horizontal trellis encircling an existing oak tree that leads out to a generous deck. [Image 13] Inside, cost-saving measures inspired by Lisl’s previous work designing prefabricated homes in the Twin Cities kept the budget to a slim $1,200. A hole cut into the wall was fitted with a metal trash can and fitted with a door to serve as an earth-chilled refrigerator. The generous hearth with stone and brick surfaces acted as both heating and cooking elements. A $50 budget for furniture spurred the architects to design a thrifty set of tables and chairs from a single piece of plywood, with cotton clotheslines strung across to form a backrest. [Image 14] These bespoke details and thoughtful construction delighted the owners and charmed their guests, an impressive roster that included Sinclair Lewis, Robert Penn Warren, and Buckminster Fuller.

Interwar years and the Great Depression were years of global cultural change and exchange, including the introduction of modernism to the US and, by way of a young couple, to Minnesota. Close and Scheu, Architects, were renamed to Elizabeth and Winston Close, Architects, upon the occasion of Elizabeth and Winston’s marriage in 1939. Elizabeth, known as Lisl, was born in 1912 to Austrian intelligentsia. She grew up steeped in early modernism and the social housing agenda of Red Vienna. Lisl’s family commissioned a modernist house designed by Adolf Loos, frequently hosted members of the Social Democrats for salons and parties, and introduced her to the potential of housing with a social agenda. In 1932 Lisl fled Austria and enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she met Winston (known as Win). With their newly attained degrees and a shared interest in modernist housing, the two moved to Minnesota and began their practice. Lisl was the first woman to be a registered architect in Minnesota, and formed the first distinctively modern architectural practice in Minnesota with Win. Despite a stint during WWII when the office was closed, the pair produced a wartime cottage design that married modernism to the rustic language of cabin culture.

Joseph and Dagmar Beach lived near the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, where Joseph was the head of the English Department. They hired the Close architecture duo to design a low-budget cabin on a hillside site in Osceola, Wisconsin. With no access road, no water, and no electricity, the site for the cabin was rustic and challenging. Cut into the ravine above the St. Croix river, Dagmar described the site as midway between sky and water. The Closes designed “Skywater” with three of the four walls embedded into the earth. From the path leading in, the structure’s sod roof, more than two feet thick with soil, and stone walls, studded with rocks picked up around the site, are invisible in the leafy forest. [Image 12] Both of these construction techniques are traditional, not modern. Lisl cited the inspiration for the sod roof, saying in 1968, “The Finns have been using sod roofs for years and the result is a natural air conditioner.” The fourth wall, facing the river, is made entirely of glass, with a cantilevered horizontal trellis encircling an existing oak tree that leads out to a generous deck. [Image 13] Inside, cost-saving measures inspired by Lisl’s previous work designing prefabricated homes in the Twin Cities kept the budget to a slim $1,200. A hole cut into the wall was fitted with a metal trash can and fitted with a door to serve as an earth-chilled refrigerator. The generous hearth with stone and brick surfaces acted as both heating and cooking elements. A $50 budget for furniture spurred the architects to design a thrifty set of tables and chairs from a single piece of plywood, with cotton clotheslines strung across to form a backrest. [Image 14] These bespoke details and thoughtful construction delighted the owners and charmed their guests, an impressive roster that included Sinclair Lewis, Robert Penn Warren, and Buckminster Fuller.

|

Image 12.

The sod roof of the 1941 cabin at Skywater blends into the surrounding, with only the natural stone chimney giving away the presence of a dwelling. Photo Courtesy Tom Trow. |

Image 13. The horizontal trellis on the deck-side of the sod cabin at skywater encircled an existing tree, until the tree outgrew the form. This trellis is said to be inspired by the Wiley House, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and located across the street from the Close’s “Opus One” house. Photo Courtesy Tom Trow. |

Image 14.

The furniture for “Skywater” was designed by Lisl Close and constructed of plywood and clothesline. This design is both a cost-saving measure and demonstration of the modernist cabin, wherein every object is designed. Photo Courtesy Tom Trow. |

The rustic modernism of the sod cabin was elaborated on twenty years later with the construction of a companion, the stilt cabin. [Image 15] Completed in 1961, the larger stilt cabin was designed with a different attitude toward the forest. Where the sod cabin hunkers into the hillside, the stilt cabin perches above it. [Image 16] Expressing the mid-century economic upswing and domestic technological innovations of the era, the stilt cabin includes electricity, running water, and a screened-in porch with a dramatic angled roof framed in wood, cantilevered over the cliffside. [Image 17] Comparing the two buildings at Skywater reveal changing views about nature. The sod cabin’s construction technique minimized store-bought materials, making the most of the site for building, simultaneously a product of material shortages and a demonstration of Great Depression-era resourcefulness. During the early twentieth century, nature was viewed as a resource to be enjoyed through use, demonstrated by the use of land as insulation and building material at the sod cabin. The stilt cabin is not built into the ground, but perched above the ground. This stance disturbs minimal soil and tree roots and provides tree canopy views. The 1961 building uses modern technology to protect and provide comfort for its occupants, enabling their access to the relaxing benefits of being in nature. These ideas of nature’s positive effects on humans and developing eco-consciousness approach to land represents midcentury attitudes about nature. [Image 18] Both cabins share a reflective attitude, framing and providing access to natural beauty for human enjoyment. The Beach family later sold Skywater to the Close family, and their descendants continue to visit in the summer, bringing friends and family along. The cabins at Skywater demonstrate ideas essential for cabin culture. Through communing with nature, a family group can relax and strengthen their bond.

|

Image 15.

The “Stilt Cabin,” in background, was constructed in 1961 as a companion to the original, 1941, “Sod Cabin.” Photo Courtesy Tom Trow. |

Image 16.

The cantilevered porch of the Stilt Cabin is supported by slim columns embedded into the hillside. Photo Courtesy Tom Trow. |

Image 17.

The screened-in porch of the Stilt Cabin frames the Sod Cabin. This view was painted by Lisl Close after the Close family gained ownership of the cabins at Skywater. Photo Courtesy Tom Trow. |

Image 18.

Constructed in 1961, the Stilt Cabin contains modern amenities that the original Sod Cabin did not, including electric heating and lighting. Photo Courtesy Tom Trow. |

Cabins as Capital

The difference in design ethos and material choice between the sod cabin and the stilt cabin at Skywater are a reflection of both the architects’ growing sophistication and historic context. The postwar building boom affected residential construction at a vast scale—whole communities were built overnight with new construction techniques, material innovation, and a market flooded with cash-rich buyers. Those prospective homeowners were often beneficiaries of government-backed mortgages. These mortgages and other housing policies of the era constructed the contemporary financial apparatus of property-as-capital, wherein a house is as much an investment as it is a home. The flaws and bias of postwar housing policies also buttressed structural racism. In the Twin Cities, redlining policies shaped neighborhoods with enduring effects on contemporary property value, school districts, and political districts that entrench members of racial and class groups in cycles of poverty. Throughout the 20th century, rates of home ownership were lower among people of color than among white people, and rates of cabin ownership were similarly correlated. Cabin culture developed primarily as a white phenomenon.

A notable exception occurred in Crow Wing County when, in the 1920s, an African-American man named George Gamble purchased land on Lake Adney. Gamble partitioned the land and sold parcels to other Black families. As so many other lakes in the region did, Lake Adney became a cottage community with small cabins built and passed on to family members. Neighbors and friends were brought up to visit and persuaded to purchase land on the lake. For a time, Lake Adney was an outpost of St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood, demonstrating how community bonds can facilitate spatial relationships. Even after Rondo was destroyed by the construction of the highway, Lake Adney remained a treasured spot for relaxation and community bonding for several generations of multiple families. For Black people at Lake Adney, the primary activity at the cabin was relaxation, being together, free from everyday worries—a powerful offer, especially for people of color facing systemic barriers and racism in cities across the United States. The political, societal, and technological changes of the 20th century caused shifts in cabin design, location, and ownership, but this emphasis on gathering, escaping from the woes of society, and relaxing in nature, is central to cabin culture across eras and communities.

The difference in design ethos and material choice between the sod cabin and the stilt cabin at Skywater are a reflection of both the architects’ growing sophistication and historic context. The postwar building boom affected residential construction at a vast scale—whole communities were built overnight with new construction techniques, material innovation, and a market flooded with cash-rich buyers. Those prospective homeowners were often beneficiaries of government-backed mortgages. These mortgages and other housing policies of the era constructed the contemporary financial apparatus of property-as-capital, wherein a house is as much an investment as it is a home. The flaws and bias of postwar housing policies also buttressed structural racism. In the Twin Cities, redlining policies shaped neighborhoods with enduring effects on contemporary property value, school districts, and political districts that entrench members of racial and class groups in cycles of poverty. Throughout the 20th century, rates of home ownership were lower among people of color than among white people, and rates of cabin ownership were similarly correlated. Cabin culture developed primarily as a white phenomenon.

A notable exception occurred in Crow Wing County when, in the 1920s, an African-American man named George Gamble purchased land on Lake Adney. Gamble partitioned the land and sold parcels to other Black families. As so many other lakes in the region did, Lake Adney became a cottage community with small cabins built and passed on to family members. Neighbors and friends were brought up to visit and persuaded to purchase land on the lake. For a time, Lake Adney was an outpost of St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood, demonstrating how community bonds can facilitate spatial relationships. Even after Rondo was destroyed by the construction of the highway, Lake Adney remained a treasured spot for relaxation and community bonding for several generations of multiple families. For Black people at Lake Adney, the primary activity at the cabin was relaxation, being together, free from everyday worries—a powerful offer, especially for people of color facing systemic barriers and racism in cities across the United States. The political, societal, and technological changes of the 20th century caused shifts in cabin design, location, and ownership, but this emphasis on gathering, escaping from the woes of society, and relaxing in nature, is central to cabin culture across eras and communities.

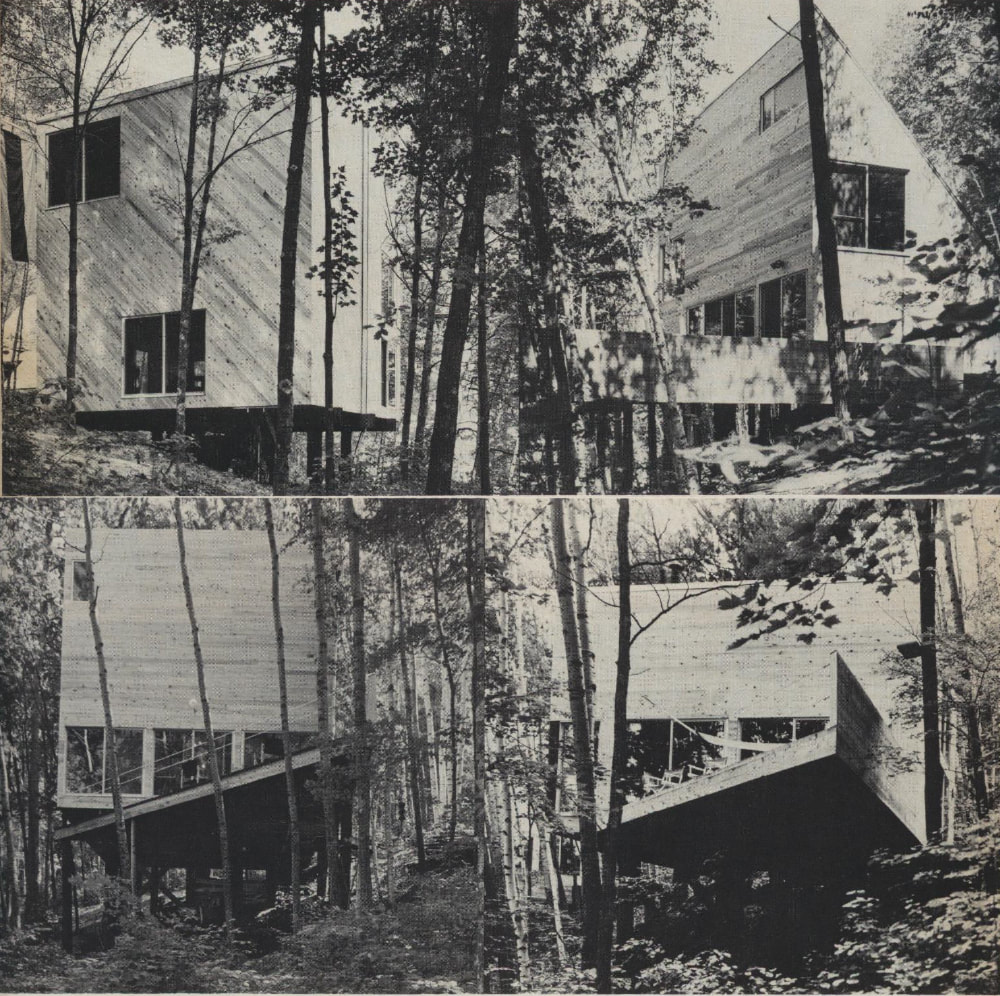

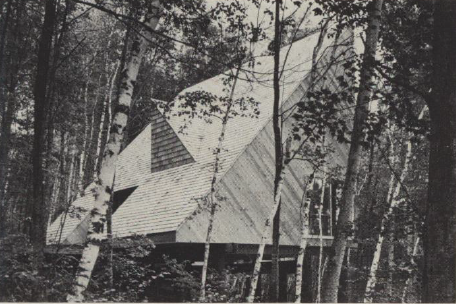

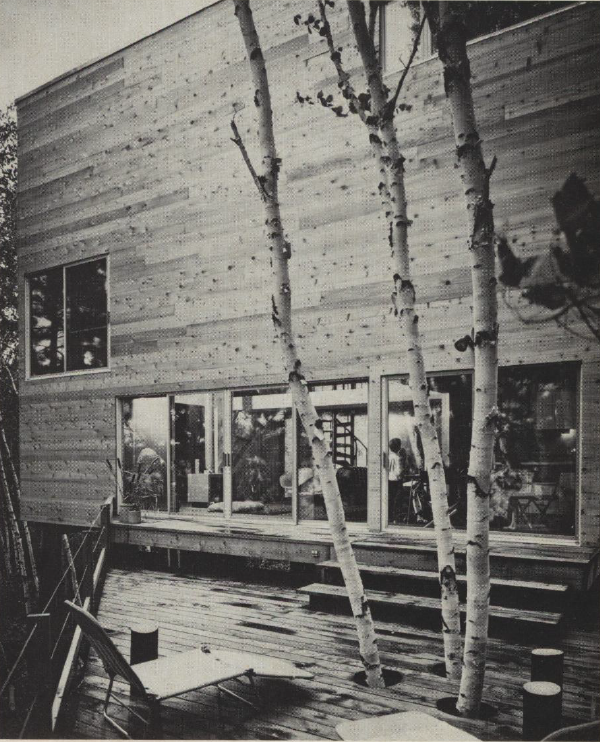

FOUR CABINS; 1970

James Stageberg, Leonard Parker, Bruce Abrahamson, and John Rauma were four prominent architects of the modernist movement in the Twin Cities. The four frequently competed for commissions in the city, yet in rural Wisconsin the architects collaborated to build a set of four cabins along a 500-foot stretch of lake shoreline. [Image 19] Stageberg, Parker, Abrahamson, and Rauma were appointed professors at the University of Minnesota School of Architecture by Ralph Rapson, who mentored and instilled a love of modernism in each of the architects. As a group, they traveled together to the east coast to visit new works by their contemporaries— Saarinen, Khan, Rudolph, Sert, and others. The mutual appreciation for modernism united the four despite their rivalry. Architectural jaunts became a family affair in 1968, when the four caravanned around the region to look at land for their collective cabin venture. The selected site is adjacent to a lake with a sandy bottom, perfect for swimming. Rauma, Abrahamson, and Parker were having dinner and decided to share their nascent designs. Without previous coordination, they drew identical shapes to represent their cabin sections—a 45-degree triangle. [Image 20] The four decided the cabins would share a common architectural language, with individual designs left up to the distinct family. As the designs developed, Stageberg demurred and said, “I tried working with the wedge form but it was not my cup of tea. Everything I did at that time had a flat roof on it.” [Image 21] Nevertheless, the coordination between the architects and the collective lifestyle that emerged from their decisions is a remarkable triumph in modernist cabin architecture.

James Stageberg, Leonard Parker, Bruce Abrahamson, and John Rauma were four prominent architects of the modernist movement in the Twin Cities. The four frequently competed for commissions in the city, yet in rural Wisconsin the architects collaborated to build a set of four cabins along a 500-foot stretch of lake shoreline. [Image 19] Stageberg, Parker, Abrahamson, and Rauma were appointed professors at the University of Minnesota School of Architecture by Ralph Rapson, who mentored and instilled a love of modernism in each of the architects. As a group, they traveled together to the east coast to visit new works by their contemporaries— Saarinen, Khan, Rudolph, Sert, and others. The mutual appreciation for modernism united the four despite their rivalry. Architectural jaunts became a family affair in 1968, when the four caravanned around the region to look at land for their collective cabin venture. The selected site is adjacent to a lake with a sandy bottom, perfect for swimming. Rauma, Abrahamson, and Parker were having dinner and decided to share their nascent designs. Without previous coordination, they drew identical shapes to represent their cabin sections—a 45-degree triangle. [Image 20] The four decided the cabins would share a common architectural language, with individual designs left up to the distinct family. As the designs developed, Stageberg demurred and said, “I tried working with the wedge form but it was not my cup of tea. Everything I did at that time had a flat roof on it.” [Image 21] Nevertheless, the coordination between the architects and the collective lifestyle that emerged from their decisions is a remarkable triumph in modernist cabin architecture.

|

Left: Image 19. The Four Cabins were profiled in Architecture Minnesota. Architects, clockwise from top left: Stageberg, Parker, Abrahamson, Rauma. Architecture Minnesota, August/September 1982. Above: Image 20. The design by Leonard Parker for his cabin stuck most faithfully to the original wedge shape agreed upon by all four architects. Architecture Minnesota, August/September 1982. |

The four cabins are a set. The selection of a Pella sliding door set the module for all of the buildings, with the aforementioned wedge form incorporated either in massing, as in Parker’s wedge, or in the shape of the deck in plan, for Stageberg’s rectangular prism. The cabins are clad, inside and out, in unvarnished cedar tongue-and-groove boards. The access road, water and electric utility, and a dock are shared among the four families. The same builder, Chester “Chet” Lambert, constructed all four cabins with impeccable workmanship. [Image 22] Each cabin perched lightly on the land, with a mutual architectural reverence toward the wooded site. [Image 23]

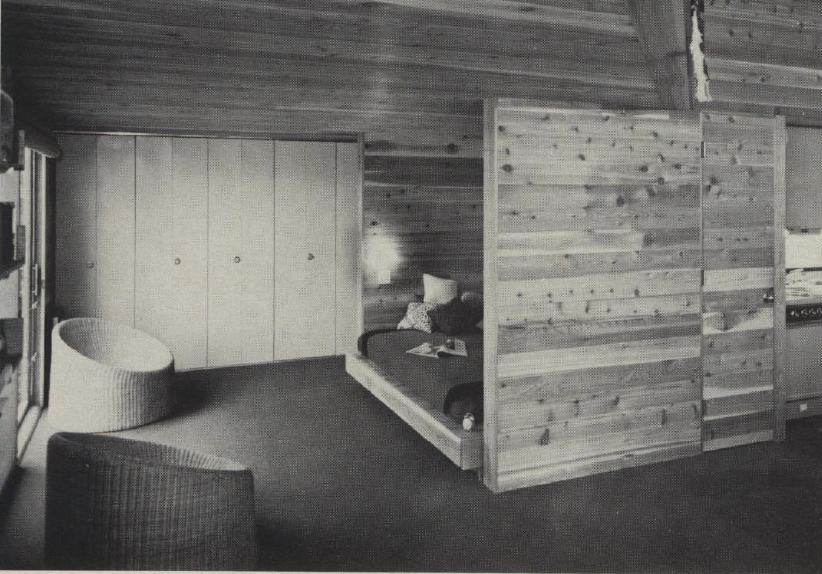

The cabins have nuance and their cohesive ruleset is extrapolated through the respective architect’s design sensibility. The Stageberg cabin maximized usable space to accommodate six children with a twist—the rectangular prism is cut with triangular floors, with stairs pressed in one corner and the opposite corner open. An open-plan concept on the ground floor is celebrated with a soaring double-height ceiling. The Parker cabin has a dramatic shed roof, with the peak of the angle occupied by a crow’s nest and two small sleeping lofts. Abrahamson’s generous deck, located off the back of the house, included holes cut out for existing trees. [Image 24] All four cabins have a tremendous amount of openness in plan, with rooms and programs flowing into each other, but Rauma expresses radical boundary-free living, with the main bedroom built into the kitchen-dining-living room of the ground floor. [Image 25, Image 26] The geometric playfulness, informal program, and shared material palette of the cabins create a sense of cohesiveness across the site.

|

Image 21.

James Stageberg’s cabin had a flat roof, in part to accommodate his large family of six children. This photograph depicts Jane Stageberg and her husband leaving after a summer vacation at the cabin. Photo Courtesy Jane Stageberg. |

Image 22.

The dining room of Stageberg’s cabin features a three-story ceiling and, at left, a painting of the builder Chet Lambert. Photo Courtesy Jane Stageberg. |

Image 23.

The Stageberg cabin demonstrates the agreed-upon technique of perching lightly on the land, shared by all four cabins. Photo Courtesy Jane Stageberg. |

Image 24.

At Bruce Abrahamson’s cabin, the deck contains cutouts for trees. All four architects shared the goal of disturbing minimal trees possible in their cabin designs. Architecture Minnesota, 1982. |

Today, three of the four cabins are still owned and visited by the original families. Jane Stageberg, architect and daughter of James Stageberg, is currently overseeing a renovation of the Stageberg cabin. The cedar wood siding is replaced, and will weather over time to match the others again. Updated windows and flashing will protect the interior of this heirloom cabin. Stageberg is working to stay as true to the original details of the cabin as possible.

As intended by the architects, the shared dock is the center of the site physically and socially. The cabins were designed for occupancy in all four seasons, with electric heating and wood fireplaces. Wintertime visitors spent days at nearby Telemark Ski Lodge. Stageberg notes the continued convivial spirit among the families, as they serendipitously encounter each other at the lake over the years. This collective attitude is a nuanced take on the usual togetherness of cabin culture; the deliberateness with which the community is constructed stands out. Stageberg recalls that, even as a child, she recognized that every part of each of the cabins was fully designed, from the silverware to the details. This total design is a hallmark of modernism, and the cabins express a holistic design in the master site plan and in the architectural and material language, down to the details. Remarkably, the casual playfulness of each of the four cabins ensures the overall effect is charming.

|

Above: Image 25.

John Rauma’s design for the cabin displays the Pella sliding door used by all four cabins. Architecture Minnesota, August/September 1982. Right: Image 26. All four cabins have an open plan, but Rauma takes the idea farthest with placement of the main bedroom right next to the kitchen, looking onto the back deck. Architecture Minnesota, August/September 1982. |

GLASS CUBE; 1974

In 1974, Ralph Rapson was at the apex of his career as Minnesota’s premier modernist architect. Rapson was head of the School of Architecture at University of Minnesota and architect of two iconic designs: the Guthrie Theater, opened in 1963 adjacent to the Walker art Center, and Cedar Square West, opened in 1973 to change the Twin Cities’ skyline with its color-blocked facade. In 1974, Rapson procured land on the Apple River near Amery, WI. The site had an existing primitive cabin, with outhouse and hand pump. With only himself, his wife, Mary, and their young family to please, Rapson was free to experiment with the design of the cabin. The family walked the site and identified two possible locations for the cabin: one was dismissed as being too close to the road, leaving the second location, atop a hill, nearly 120 feet above the Apple River. From this vantage point, Rapson decided that the cabin should include the ability to see in every direction. This cabin would be an experimental dwelling, a modernist respite from the revivalist home the Rapsons lived in in Minneapolis. Son Toby Rapson said that the cabin was intended to be “as far from a house as [Rapson] could make it.” Instead of a house, this cabin was an experimental viewing box — Rapson’s take on the modernist tradition of designing a glass dwelling. [Image 27]

In 1974, Ralph Rapson was at the apex of his career as Minnesota’s premier modernist architect. Rapson was head of the School of Architecture at University of Minnesota and architect of two iconic designs: the Guthrie Theater, opened in 1963 adjacent to the Walker art Center, and Cedar Square West, opened in 1973 to change the Twin Cities’ skyline with its color-blocked facade. In 1974, Rapson procured land on the Apple River near Amery, WI. The site had an existing primitive cabin, with outhouse and hand pump. With only himself, his wife, Mary, and their young family to please, Rapson was free to experiment with the design of the cabin. The family walked the site and identified two possible locations for the cabin: one was dismissed as being too close to the road, leaving the second location, atop a hill, nearly 120 feet above the Apple River. From this vantage point, Rapson decided that the cabin should include the ability to see in every direction. This cabin would be an experimental dwelling, a modernist respite from the revivalist home the Rapsons lived in in Minneapolis. Son Toby Rapson said that the cabin was intended to be “as far from a house as [Rapson] could make it.” Instead of a house, this cabin was an experimental viewing box — Rapson’s take on the modernist tradition of designing a glass dwelling. [Image 27]

Image 27.

The experimental Glass Cube house has views to the bucolic site on all sides. Photo Courtesy Corey Gaffer.

The experimental Glass Cube house has views to the bucolic site on all sides. Photo Courtesy Corey Gaffer.

The Glass Cube was designed as a cube within a cube. Rapson had long been interested in exploring pure forms, and assigned his students to design projects within a studio dedicated to the mathematical tautology “1x1x1=1.” The exterior cube is windowless, a black frame providing lateral bracing, stiffened by steel cables crossed in tension. [Image 28] The inner cube is all glass, comprising 48 Anderson windows and 8 Anderson doors, as an advertisement in Progressive Architecture proclaimed. The white mullions of this inner cube set up visual tension as the regular window grid juxtaposes with the black outer shell and inner floors, suspended in the interior like lilly pads, each system with its own spatial logic. Minneapolis architect Eric Amel praises these differing vantage points, writing, “[the] occupant levitates through the volume of space and senses the parallax of shifting vantage points to the site and horizon.” The building is constructed entirely with standardized materials—another lifelong interest of Rapson, who designed a fabric ready-made building while studying at Cranbrook in 1941. The store-bought materials aided construction as, once the builder was able to bring materials to the remote site, the building went up extremely quickly. One wall was completed per day. Following construction, the textures and colors of the activities within the building brightened the facade, bringing the inside out just as the interior experience brings the outside in. Rapson wanted to be immersed in nature while at the cabin, but preferred a pane of glass between himself and “all those little crawly, squirmy things,” as he said at the time of construction.

The Glass Cube is distinctly not a house. Instead, it is closer to an experiment—a virtue of both the architect being his own client and the relative privacy from neighbors. The Glass Cube may be considered an experiment in flexibility. On the interior, the only fixed programs are the prefabricated kitchen and bathroom systems. [Image 29] The suspended floors are designed for flexibility of use and maximizing views to the outside. [Image 30] Privacy is not a primary concern for this cabin. When the Rapsons first visited the site, there were few trees but no neighbors for miles. As the family visited in summers to come, they planted (or rather, asked architecture students to plant) trees around the site. To their surprise, nearly all of the hundreds of seedlings planted flourished on the now heavily-forested site. This flexibility in the program is an architect’s dream, one Rapson masterfully took advantage of in this experiment.

The Glass Cube is, however, distinctly a cabin. The building is not intended to be used during the winter, an easy rebuttal to any aghast viewer thinking about the winter heating bills. For the bumper seasons, Rapson designed the ground floor of the Glass Cube to act as a thermal mass. Rather than a solid wooden floor, the occupiable areas are reduced to small rafts, floating in a sea of marble chips. [Image 31, Image 32] The marble chips are thought to be a thermal mass that absorbs the sunlight during the day and releases it at night. However, Toby Rapson thinks the marble chips are more effective as an experiential design element. To Toby, the marble chips and the floor pads within them are meant to remind the user to slow down, like navigating stepping stones in a river.

The Glass Cube is, however, distinctly a cabin. The building is not intended to be used during the winter, an easy rebuttal to any aghast viewer thinking about the winter heating bills. For the bumper seasons, Rapson designed the ground floor of the Glass Cube to act as a thermal mass. Rather than a solid wooden floor, the occupiable areas are reduced to small rafts, floating in a sea of marble chips. [Image 31, Image 32] The marble chips are thought to be a thermal mass that absorbs the sunlight during the day and releases it at night. However, Toby Rapson thinks the marble chips are more effective as an experiential design element. To Toby, the marble chips and the floor pads within them are meant to remind the user to slow down, like navigating stepping stones in a river.

|

Image 30.

The upper levels, suspended like floating pads, are reached via a spiral staircase. The entire building is supported with the walls and just one column. Photo by Corey Gaffer |

Image 31.

Marble chips create a unique experience for circulation on the ground floor, as the viewer must navigate stepping between floor pads. Photo by Corey Gaffer |

The Rapson family still owns and frequently visits the Glass Cube in the summer for a distinctly modern cabin experience. This cabin certainly does not blend into its surroundings in the same way a rustic building made of local materials does, and as such, collects visitors and architectural enthusiasts in great quantity. At night, the cabin lights up like a lantern and the outside vanishes—the windows instead reflect the interior back at the occupants. [Image 33] One such evening surprised the Rapsons. As they played cards inside, they heard rustling and looked out to see three-dozen eyes staring back, watching their game intently. The neighbor’s cows had gotten loose and came by to see the Glass Cube, lit up like a beacon. The Glass Cube does its job wonderfully, protecting the inhabitants from the cow visitors and providing a getaway for the family.

The Modernist Cabin

As a modernist cabin, the Glass Cube stands out as an interpretation of the typical program of a cabin refracted through the modernist lens. The use of industrial materials to create a flexible interior and the use of a geometric and innovative structural system are hallmarks of the modernist movement; Rapson, at the height of his talent, reinterpreted these modernist themes with thoughtful and playful touches. The Glass Cube is an heirloom cabin, designed specifically for the family and passed down through generations. This is commonplace for both architect-designed and vernacular cabins, and serves as an explanation for the enduring quality of cabin culture as it relates to family, gathering, and nostalgia. The precipitous rise in quality of life and family wealth that occurred for white Americans in the postwar period benefited cabin culture, as more families were able to build their own cabin. This building boom, in both the city and the country, benefited architects. As modern architecture picked up steam, many architects were able to design their own cabins in the 1970s. It is through these historic and economic machinations that the modernist cabin evolved as a beneficiary of building booms from postwar demand and urban renewal.

As these historic events fade into the past, there is an impending shift in ownership for Minnesota’s cabins. In 2016, the average age of a cabin owner in Minnesota was 68, a number up from previous years. As cabins are passed on to younger generations, the change in ownership will have effects on cabin culture, allowing more individuals to experience life at the lake and bringing questions about the nature of property. Lakeshore property in particular commands high prices in the region. As the price of property goes up, landowners are likely to build correspondingly high-priced cabins—perhaps more like lake homes, with amenities and heating for year round occupancy. The modernist cabins, valuable for their design as much as their property, may undergo changes as their original, no-frills designs age through years of freeze-and-thaw cycles and younger generations develop their own cabin culture.

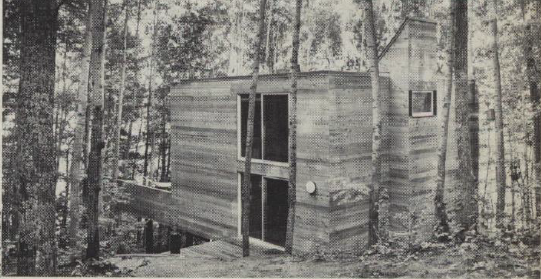

MILO H. THOMPSON CABIN; 1977

Just as cabins share no common style, modernist cabins share no common form. As the late modern trend of pure forms cooled down, postmodern architecture elaborated on traditional forms, using playful tessellations and bright colors to break from the industrial, neutral scheme of earlier modernist buildings. Milo H. Thompson, a Minneapolis architect known for the playful bandshell at Bde Unma (Lake Harriet, bandshell constructed 1986), studied at the School of Architecture while Ralph Rapson was head of school. In practice, Thompson’s work extrapolates on high modernism with exaggerated, sculptural forms and colorful materials, demonstrating late modernist tendencies that begat postmodernism. In 1977, Thompson designed a cabin for his own family. Like Rapson, Stageberg, Parker, Rauma, and Abrahamson before him, Thompson used the occasion of his own cabin design as a chance to experiment with new ideas.

The resulting dwelling is tower-like, with five occupiable levels and a chimney extending to form a twisted, rectangular peak that intersects with the pyramidal hipped roof. [Image 34] The cabin nearly breaks zoning limits in its Big Woods location, but chimneys are an exception. The tall and narrow form of the building derives from Thompson’s desire to disturb the smallest possible area on the site, as well as a desire to maximize passive heating and cooling potential. Heating units are placed below windows on the lower floors, and the tall ceilings and open floor plates create a natural-stack action that distributes heat vertically. Louvers at the attic level operate in the summer to allow warm air an escape. This passive environmental design is meant to allow for maximum interior comfort with minimal systems: there are no fans and less electricity required in a natural-stack system.

The Milo H. Thompson cabin’s unique form and inventive system demonstrates changing ideas for the modernist cabin. Like the Naniboujou Lodge, built fifty years prior, the bright colors and playful form of the Thompson cabin are a riff on chateauesque revival style, with the volume turned up for contemporary audiences. [Image35] The use of natural stone from the site to form the Thompson cabin’s ground level wall is akin to Skywater’s material use and burrowing into the site. Like the Four Cabins and Glass Cube, Thompson’s cabin is an introspective retreat for creative recharging, its modern systems protecting the interior from nature while still permitting access. The incorporation of passive environmental systems at the Thompson cabin suggests a new environmentalism. Following the oil crises in the earlier 1970s, the choice of passive system and electric heaters represent a move away from fossil fuels and a new consciousness towards the environment. The modernist cabin promised access to nature. Perhaps through this unprecedented access, the next generation of architects may design with an attitude increasingly protective of nature.

Just as cabins share no common style, modernist cabins share no common form. As the late modern trend of pure forms cooled down, postmodern architecture elaborated on traditional forms, using playful tessellations and bright colors to break from the industrial, neutral scheme of earlier modernist buildings. Milo H. Thompson, a Minneapolis architect known for the playful bandshell at Bde Unma (Lake Harriet, bandshell constructed 1986), studied at the School of Architecture while Ralph Rapson was head of school. In practice, Thompson’s work extrapolates on high modernism with exaggerated, sculptural forms and colorful materials, demonstrating late modernist tendencies that begat postmodernism. In 1977, Thompson designed a cabin for his own family. Like Rapson, Stageberg, Parker, Rauma, and Abrahamson before him, Thompson used the occasion of his own cabin design as a chance to experiment with new ideas.

The resulting dwelling is tower-like, with five occupiable levels and a chimney extending to form a twisted, rectangular peak that intersects with the pyramidal hipped roof. [Image 34] The cabin nearly breaks zoning limits in its Big Woods location, but chimneys are an exception. The tall and narrow form of the building derives from Thompson’s desire to disturb the smallest possible area on the site, as well as a desire to maximize passive heating and cooling potential. Heating units are placed below windows on the lower floors, and the tall ceilings and open floor plates create a natural-stack action that distributes heat vertically. Louvers at the attic level operate in the summer to allow warm air an escape. This passive environmental design is meant to allow for maximum interior comfort with minimal systems: there are no fans and less electricity required in a natural-stack system.

The Milo H. Thompson cabin’s unique form and inventive system demonstrates changing ideas for the modernist cabin. Like the Naniboujou Lodge, built fifty years prior, the bright colors and playful form of the Thompson cabin are a riff on chateauesque revival style, with the volume turned up for contemporary audiences. [Image35] The use of natural stone from the site to form the Thompson cabin’s ground level wall is akin to Skywater’s material use and burrowing into the site. Like the Four Cabins and Glass Cube, Thompson’s cabin is an introspective retreat for creative recharging, its modern systems protecting the interior from nature while still permitting access. The incorporation of passive environmental systems at the Thompson cabin suggests a new environmentalism. Following the oil crises in the earlier 1970s, the choice of passive system and electric heaters represent a move away from fossil fuels and a new consciousness towards the environment. The modernist cabin promised access to nature. Perhaps through this unprecedented access, the next generation of architects may design with an attitude increasingly protective of nature.

|

Above: Image 34.

The five occupiable levels and chimney of the Milo H. Thompson extend nearly to the limits of zoning in Deerwood, MN. Photo Courtesy Bobak Ha’Eri. Right: Image 35. The tessellated geometry and bright colors of the Milo H. Thompson cabin stand out in the woods. Photo Courtesy Dale Mulfinger. |

|

CONCLUSION

Cabin culture, with its rustic connotation and emphasis on nature, may at first seem at odds with modernism, the style of urbane architects that emphasizes technology. The modernist cabin reconciles this opposition, and within the tension there is beauty. The modernist cabin immerses its occupants in nature, providing a protected space for introspective reflection. The modernist cabin also has a simple or flexible program, with the majority of space given for communal activities, like the giant dining room of Naniboujou Club Lodge or the generous decks of the Four Cabins.

The shifting historic context caused a different interpretation of the modernist cabin. Access affected the location of recreational activities and the time spent at those remote locations. Material shortages and availability changed the way cabins looked and were built. Financial and political shifts allowed more families to acquire a cabin of their own as the century went on, leaving the communal lodge behind as the single-family cabin gained popularity. Changing societal norms and family structures change who cabins are for, with greater diversity of populations now having access to outdoor recreation and younger generations inheriting heirloom cabins.

Relationship to nature is the central question for cabin architecture and cabin culture. Whether the cabin blends in, like the sod cabin at Skywater that extends the hill to form an insulating roof, or stands out, like the tall tower Milo H. Thompson designed in 1977, the modernist cabin must take a stance about the aesthetic relationship to nature. In the early modern era, conquering nature through industrial processes enabled the origin of cabin culture, like early tourists seeking respite and health through a rustic-yet-refined retreat at Naniboujou Club Lodge. These same industrial processes, perfected through generations of science and war, enable the technological design language of high modernism, as displayed with the off-the-shelf parts used in Rapson’s Glass Cube. The key value of cabin culture is togetherness, whether it is together with Nature in quiet introspection, or together with family groups. Four Cabins in Amery, a gathering of four friendly architects and their respective families, represents the collective ideal of cabin culture -- getting together, getting away from it all.

More Cabin Culture Resources from Docomomo US/MN:

– Cabin Culture! – A Virtual Road Trip

– Thunderhead

Cabin culture, with its rustic connotation and emphasis on nature, may at first seem at odds with modernism, the style of urbane architects that emphasizes technology. The modernist cabin reconciles this opposition, and within the tension there is beauty. The modernist cabin immerses its occupants in nature, providing a protected space for introspective reflection. The modernist cabin also has a simple or flexible program, with the majority of space given for communal activities, like the giant dining room of Naniboujou Club Lodge or the generous decks of the Four Cabins.

The shifting historic context caused a different interpretation of the modernist cabin. Access affected the location of recreational activities and the time spent at those remote locations. Material shortages and availability changed the way cabins looked and were built. Financial and political shifts allowed more families to acquire a cabin of their own as the century went on, leaving the communal lodge behind as the single-family cabin gained popularity. Changing societal norms and family structures change who cabins are for, with greater diversity of populations now having access to outdoor recreation and younger generations inheriting heirloom cabins.

Relationship to nature is the central question for cabin architecture and cabin culture. Whether the cabin blends in, like the sod cabin at Skywater that extends the hill to form an insulating roof, or stands out, like the tall tower Milo H. Thompson designed in 1977, the modernist cabin must take a stance about the aesthetic relationship to nature. In the early modern era, conquering nature through industrial processes enabled the origin of cabin culture, like early tourists seeking respite and health through a rustic-yet-refined retreat at Naniboujou Club Lodge. These same industrial processes, perfected through generations of science and war, enable the technological design language of high modernism, as displayed with the off-the-shelf parts used in Rapson’s Glass Cube. The key value of cabin culture is togetherness, whether it is together with Nature in quiet introspection, or together with family groups. Four Cabins in Amery, a gathering of four friendly architects and their respective families, represents the collective ideal of cabin culture -- getting together, getting away from it all.

More Cabin Culture Resources from Docomomo US/MN:

– Cabin Culture! – A Virtual Road Trip

– Thunderhead

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Award of Merit.” Housing Vol 56 (2), August 1979.

“Cabin, St. Croix River, Minnesota.” Progressive Architecture, Volume 20: 12. December 1948.

“Four cabins fit four families.” Architecture Minnesota Vol 8 (4), August/September 1982, 38-43

“Four Wisconsin Homes.” Progressive Architecture, Volume 10: 74. 1974.

Amel, Eric. ‘Glass Cube’. Email. July 26, 2021.

Anderson, Rolf T. Minneapolis. “Scenic State Park CCC/Rustic Style Historic Resources.” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form. August 29, 1988.

Burke, Evelyn. “Cabin In Side of Hill is Hermit’s Dream.” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune. May 16, 1948.

Hession, Jane K. Elizabeth Scheu Close : a life in modern architecture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Hession, Jane King, Rip Rapson, Bruce N. Wright, Afton Historical Society Press, and Campbell-Logan Bindery. Ralph Rapson : Sixty Years of Modern Design. Afton, Minn.: Afton Historical Society Press, 1999.

Kaul, Greta. “The uncertain future of cabins in Minnesota.” Minnpost, April 27, 2018. https://www.minnpost.com/economic-vitality-in-greater-minnesota/2018/04/uncertain-future-cabins-minnesota/

Lake Adney Oral History Project. Oral History Interviews of the Lake Adney Oral History Project. Minnesota Historical Society. Interview with Nathaniel Khaliq, January 5, 2017.

Lanegran, David A. "Minnesota: Nature's Playground." Daedalus 129, no. 3 (2000): 81-100. Accessed May 4, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027648.

Mack, Linda. "A Glass House, and what a View ; Ralph Rapson's Experimental 24-Foot Cube Puts Him Closer to Nature.: [METRO Edition]." Star Tribune, Sep 01, 2002.

Mulfinger, Dale. Cabinology : A Handbook to Your Private Hideaway. Newtown, CT: Taunton Press, 2008.

Mulfinger, Dale. Interview by Mary Begley. Phone interview. Minnesota, July 23, 2021.

Nelson, Charles W. and Mark e. Haidet. “Naniboujou Club Lodge.” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form. Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, May 5, 1982.

Ramey, Tim. Interview by Mary Begley. Phone interview. Minnesota, July 12, 2021.

Rapson, Toby. Interview by Mary Begley. Phone interview. Minnesota, July 13, 2021.

Shapiro, Aaron. The Lure of the North Woods: Cultivating Tourism in the Upper Midwest. University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Sommer, Lawrence J. (Project Director). “Historical Overview of Duluth’s Development”. St. Louis County Historical Society. September 1984. https://duluthmn.gov/media/5700/dhrs1.pdf

Stageberg, James, and Susan Allen, Toth. A House of One's Own : An Architect's Guide to Designing the House of Your Dreams. 1st ed. New York: C. Potter, 1991.

Stageberg, Jane. Interview by Mary Begley. Phone interview. Minnesota, July 27, 2021.

Striner, Richard. "Art Deco: Polemics and Synthesis." Winterthur Portfolio 25, no. 1 (1990): 21-34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1181301.

Trow, Tom. In conversation with Mary Begley. Phone. Minnesota, July 2021.

“Award of Merit.” Housing Vol 56 (2), August 1979.

“Cabin, St. Croix River, Minnesota.” Progressive Architecture, Volume 20: 12. December 1948.

“Four cabins fit four families.” Architecture Minnesota Vol 8 (4), August/September 1982, 38-43

“Four Wisconsin Homes.” Progressive Architecture, Volume 10: 74. 1974.

Amel, Eric. ‘Glass Cube’. Email. July 26, 2021.

Anderson, Rolf T. Minneapolis. “Scenic State Park CCC/Rustic Style Historic Resources.” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form. August 29, 1988.

Burke, Evelyn. “Cabin In Side of Hill is Hermit’s Dream.” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune. May 16, 1948.

Hession, Jane K. Elizabeth Scheu Close : a life in modern architecture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Hession, Jane King, Rip Rapson, Bruce N. Wright, Afton Historical Society Press, and Campbell-Logan Bindery. Ralph Rapson : Sixty Years of Modern Design. Afton, Minn.: Afton Historical Society Press, 1999.

Kaul, Greta. “The uncertain future of cabins in Minnesota.” Minnpost, April 27, 2018. https://www.minnpost.com/economic-vitality-in-greater-minnesota/2018/04/uncertain-future-cabins-minnesota/

Lake Adney Oral History Project. Oral History Interviews of the Lake Adney Oral History Project. Minnesota Historical Society. Interview with Nathaniel Khaliq, January 5, 2017.

Lanegran, David A. "Minnesota: Nature's Playground." Daedalus 129, no. 3 (2000): 81-100. Accessed May 4, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027648.

Mack, Linda. "A Glass House, and what a View ; Ralph Rapson's Experimental 24-Foot Cube Puts Him Closer to Nature.: [METRO Edition]." Star Tribune, Sep 01, 2002.

Mulfinger, Dale. Cabinology : A Handbook to Your Private Hideaway. Newtown, CT: Taunton Press, 2008.

Mulfinger, Dale. Interview by Mary Begley. Phone interview. Minnesota, July 23, 2021.

Nelson, Charles W. and Mark e. Haidet. “Naniboujou Club Lodge.” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form. Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, May 5, 1982.

Ramey, Tim. Interview by Mary Begley. Phone interview. Minnesota, July 12, 2021.

Rapson, Toby. Interview by Mary Begley. Phone interview. Minnesota, July 13, 2021.

Shapiro, Aaron. The Lure of the North Woods: Cultivating Tourism in the Upper Midwest. University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Sommer, Lawrence J. (Project Director). “Historical Overview of Duluth’s Development”. St. Louis County Historical Society. September 1984. https://duluthmn.gov/media/5700/dhrs1.pdf

Stageberg, James, and Susan Allen, Toth. A House of One's Own : An Architect's Guide to Designing the House of Your Dreams. 1st ed. New York: C. Potter, 1991.

Stageberg, Jane. Interview by Mary Begley. Phone interview. Minnesota, July 27, 2021.

Striner, Richard. "Art Deco: Polemics and Synthesis." Winterthur Portfolio 25, no. 1 (1990): 21-34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1181301.

Trow, Tom. In conversation with Mary Begley. Phone. Minnesota, July 2021.